The new challenges of the Italian education system

Italy is not keeping pace with OECD countries and is embracing professional degrees

Italy – as emerges from the OECD study entitled “Education at a Glance” – spends on average less than other countries on education: 3.9% of GDP, against the average 5% of industrialized countries and 4.6% of European Union countries. What are the immediate implications of the Italian education policy?

In 2018, the number of 30-34 year-olds with university degrees was the second lowest in the EU (26.9%), well below the EU average, which stands at 39.9%. In addition, Italian graduates are increasingly looking for work abroad: in 2017 28,000 graduates moved, a figure that in sharp growth compared to previous years.

We see differences compared to the rest of Europe also in terms of skills and educational level. In Italy, 27.9% of young people aged 30-34 holds a higher education degree. The national target set by the Europa 2020 strategy (26-27%) has thus been largely achieved. However, the level remains much lower than the European average and only higher than that of Romania. For women, the share of 30-34 year-olds with university degrees is 34%, for men 21.7%.

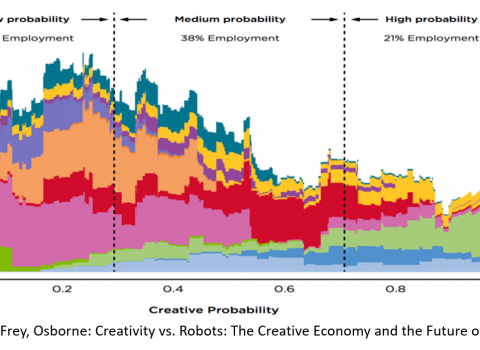

From the 2000s onwards, the European Commission has indicated the objectives for the development of an education and training of excellence, focusing above all on the diffusion of forms of dual learning, i.e. capable of combining theoretical learning with the acquisition of practical skills in the workplace, thus avoiding the skill mismatch that is widespread throughout the old continent.

These skills gaps can also be seen from the opposite perspective, when people are overtrained and overqualified to perform a certain type of job: having too many skills as well as not having the right ones is a double problem. This means that, on the one hand, the resources invested in education and training go to waste and that the too many courses available are not connected with placement activities and market demands; on the other hand, the communication channels for jobs, as well as the recruiting techniques are not efficient. The way companies or employment agencies communicate, despite the high level of digitization and social recruiting, does not guarantee the effective match between supply and demand.

The recent proposal advanced by the National Council of University Students aimed at abolishing the prohibition of double enrollment and favoring the introduction of multidisciplinary courses, is part of a framework of actions aimed at strengthening the current Italian university system.

These proposals have been developed starting from students’ requests, taking virtuous examples of foreign universities as a model and trying to imagine a concrete implementation of these policies in Italy.

In light of these proposals, the next Italian graduates will be able to have a multidisciplinary background, will be able to apply technology education to the humanities or enroll in both the Conservatory and the University, cultivate their love for music and study engineering.

Furthermore, in Italy the experimentation of a new type of professional degree was started in 2018/19. Fourteen three-year degree courses have been launched in as many universities, equally distributed throughout the country, which offer 700 seats in total. The goal is to train highly specialized professionals with skills in engineering, construction and environment, energy and transportation, in close collaboration with professional associations. Studies consist of two academic years plus one year of work-based learning. With their strong orientation to professions, the new professional degrees are a positive step towards the creation of a non-academic higher education program, an education sector that the Italian system lacked.

Another challenge launched to modernize the higher education system is the National Doctorate in AI (Artificial Intelligence) introduced as of the academic year 2021/2022. The goal is to create a competitive system on a global scale capable not only of retaining the best graduates in Italy, but also of attracting talent from abroad. Italy must restart from research, digital technologies and artificial intelligence, which are crucial sectors for the future of the country. It has been estimated that the industry will lead to a growth of 16% in world GDP by 2030 and will have an impact on 70% of companies.

Ultimately, by opening new paths and providing multiple training opportunities for students, it will be possible to have a positive impact on the school dropout rate and, in fact, contribute to an increase in the higher education rate. The hope is that Italy will strive to bridge the gap it has created with other advanced countries in the world, since investment in human capital is the only way to reduce or combat existing social inequality.