Trentino bombings

There is little trace in Kessler's papers of the early part of his life, which remains in the background of an important political career: however, some of the experience of the bombings in World War II remains.

Reconstructing a person’s life is not easy, especially the early years often remain the most vague. Even for important figures such as Bruno Kessler, one may not necessarily find much, all the more so if the family of origin was not known. So I am trying to retrace his steps by contacting all the archives that I think might store documents that pertained to him or his family.

The main problem, however, is that not all of them are available. If one wants to study Kessler’s early work, for example, one would have to look at the archives of the Court of Trento, where he was a court clerk more or less from 1949 to 1952, but it is not possible to do so because those documents have not yet been deposited in the State Archives of Trento and are still stored in the four warehouses of the court. One would also have to see the papers of the Banca di Trento e di Bolzano, but in this case only the minutes of the Board of Directors are available, which obviously do not cover a mere clerk in the legal department, what the protagonist of my research was from about 1952 to 1956.

Kessler’s private papers, the ones we are exploring, do not offer many insights into the first period of his life, namely the one preceding his first election as a provincial councilor in 1956, which would later see him among the protagonists of the new Council as Vice-President of the Province and Councillor for Finance.

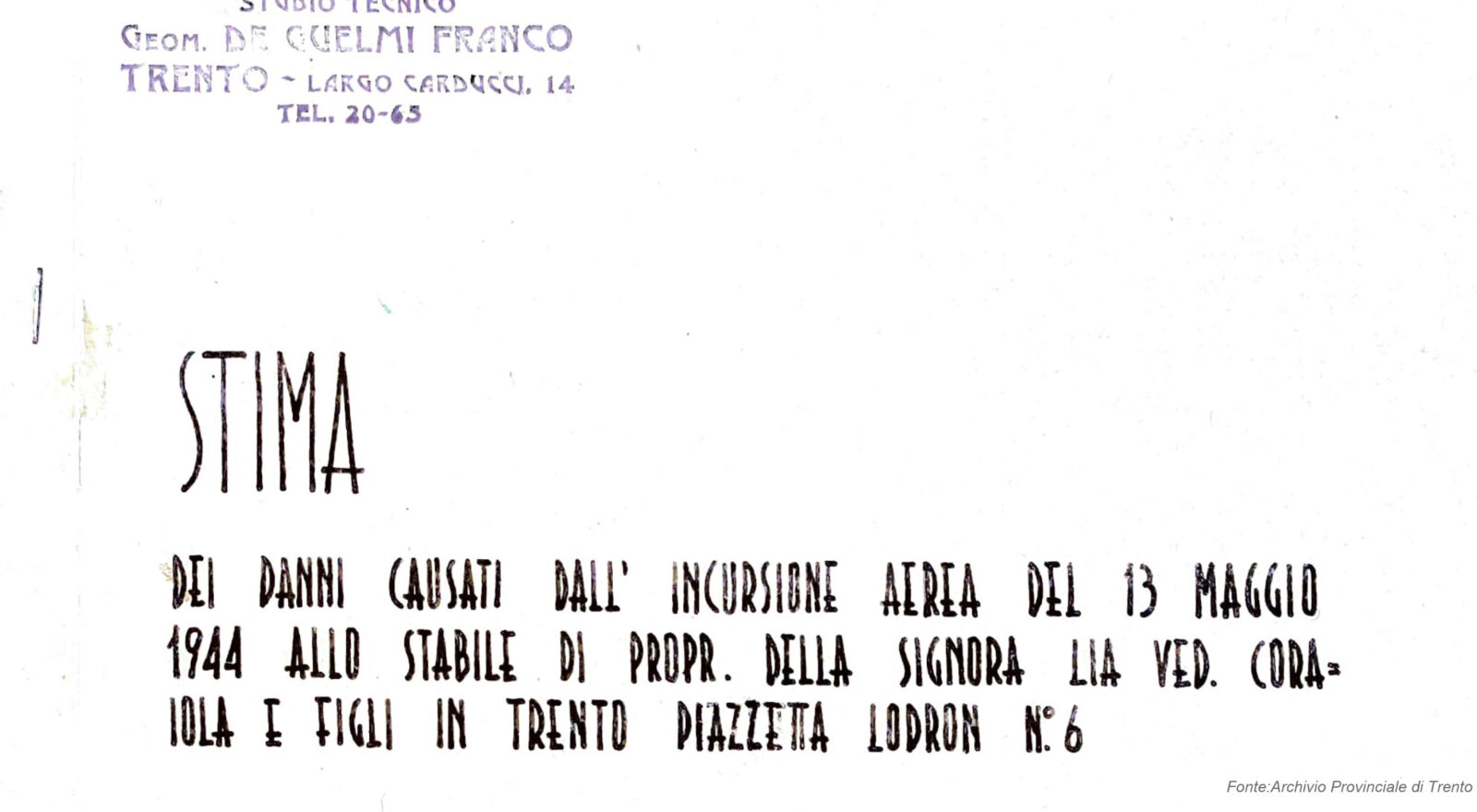

So, I tried to rummage through the oldest envelopes, such as those of the law firm that Kessler had opened, probably after he quit the Bank. Three envelopes contain many case files followed by Kessler, first as a prosecutor and then as a lawyer. These are mainly property matters: leases, purchases and sales, and mostly involve Val di Sole residents, reflecting his strong ties to his home valley. Among these, however, the file “Lia Coraiola and children in Trento” jumped out at me. Coraiola was the last name of Kessler’s mother-in-law, and in fact the file concerns the claim, filed as a result of damage caused by the May 13, 1944 bombing of the family home. The document contains the damage estimate made in September 1944 and the building’s perspective drawing. The building overlooked Piazzetta Lodron, only the tip of today’s square of the same name, which exists today precisely because of that bombing: the clearing of the buildings destroyed in fact allowed the creation of the public space we know today.

World War II left wounds in the city and province of Trento. There are many accounts of the bombings, especially of the two most devastating ones: on September 2, 1943, 229 people lost their lives and the center of the city was hit, where the San Lorenzo bridge was torn down; on May 13, 1944, the destruction was more extensive and 15,396 people were displaced. I think many Trentino families have memories of those difficult days, certainly mine did, and some have come far, such as the one that led to the creation of the animated film Mila (available on RaiPlay, you can also find the presentation held at ISIG here).

Bruno Kessler and his wife Cecilia Tomasoni had also experienced at first hand the destruction caused by those bombs. As emerges from the papers of Kessler the lawyer, Cecilia had lost her family home. Bruno, on the other hand, was on guard duty at the Pont dei Vodi, the railroad bridge on the Brenner line in Lavis (north of Trento) where, on behalf of Todt Company – the forced labor agency of Nazi Germany for which he had probably been recruited through the call to arms – he had the task of activating smoke bombs to prevent air attacks on such an important connection. The Pont dei Vodi was a major target of air campaigns: between 1943 and 1945 it suffered more than 240 bombings only to be promptly rebuilt each time. Even during one of Kessler’s shifts the bridge was destroyed, partly because he and his comrades did not light the smoke bombs, believing that the American planes were heading for Munich. By the time the aircraft changed course it was too late to save the bridge.

Europe in 1945 was a pile of rubble to be rebuilt. In its own small way, Trentino also fit into this story, and Kessler was undoubtedly one of its protagonists.