Macroscopic Quantum Tunnelling

Understanding the 2025 Nobel prize of John Clarke, Michel Devoret and John Martinis "for the discovery of macroscopic quantum mechanical tunnelling and energy quantisation in an electric circuit"

Brilliant quantum experiments are happening across all fields of physics, from high energy accelerators to magnetism and optics. These have led to a deep understanding of the subatomic world, but also to medical machines and therapies, or to ultrafast communication, and the list could go on.

What these experiments have in common is that researchers must work with the fundamental properties nature provides—the fixed gyromagnetic ratio of an electron, the discrete energy levels of an atom, or the given cross-section of a fundamental interaction*. With superconducting circuits, these properties don’t have to be merely accepted and used; they can be decided. When I explain what makes quantum circuits such a vibrant field of research, I always point to a crucial factor: our ability to engineer them. This design freedom is what truly sets them apart, and today, no other quantum system can be devised and controlled with greater precision than a superconducting circuit.

But why is that? How can no other technological platform achieve what superconducting circuits do? The answer is simple: their size. To understand this, let’s go back to the discovery of quantum tunneling. We need to explore why that was such an important discovery, and why it is equally profound to observe this same effect in an engineered circuit.

Let’s start with light bulbs. When we turn on a light bulb, a current flows through a filament which emits light. It was almost immediately clear to the scientists of light that this was not the only thing flowing out of the filament. By placing a piece of metal nearby —but not touching— the filament, they could measure an electrical current flowing through the vacuum. This meant some electrical charge (electrons) was flowing from the filament to the piece of metal without an electrical contact. The only explanation was that the filament was not only emitting light, but also electrons. However, there was a problem: electrons should not have enough energy to escape from the filament, even if it was incandescent.

In a world where the electron is a point, a small rigid object which is in a very specific place, this would have been impossible, but in our world, electrons are no such thing. According to the laws of quantum mechanics it is much more difficult to imagine what an electron truly is, and physicists describe it using a so-called wavefunction, a more wavy and quirky thing if compared to a hard sphere. Such a thing is much more blurry, for instance it does not need to have a precise position or energy, and therefore it has a better chance of escaping the filament. How so?

Imagine looking at the ocean, standing on the rocks. It’s a windy day, and the waves in front of you are breaking on the rocks. Even if your feet do not get wet, as the waves are not tall enough, you still see some waves behind you, although much lower. This is because the rocks are not a perfect, impassable barrier; part of the wave’s energy effectively penetrates it, allowing a new, lower wave to form on the other side. A quantum particle behaves in a similar way, even if a barrier is too high to surpass, it still has a chance of making it. However, unlike a wave, a particle can either go through or not, there’s no in between. Over the years, physicists have familiarized themselves with the bizarre nature of quantum mechanics, and accepted that the tiniest physical objects, roughly the size of an atom, simply behave like this. This is a very interesting phenomenon to study. It has been observed in many different ways, and it has been used to explain several unexpected observations, like the radioactive alpha decay of nuclei.

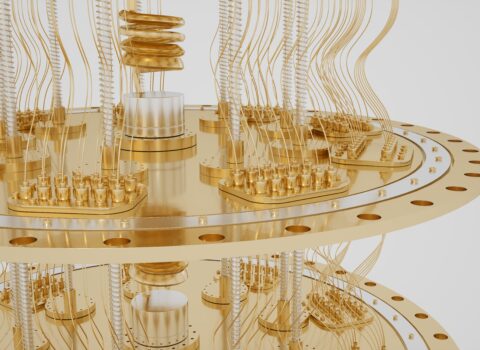

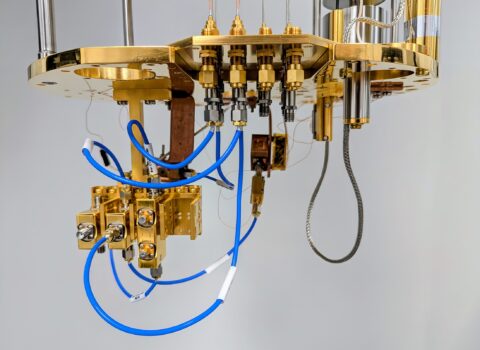

When performing an experiment, we can create exotic particles which only exist for a few billionths of a second, excite an atom —or more generally a particle— twist it and even break it. However, we cannot engineer it. But is there a chance to observe quantum effects at a much larger scale, one which we can control with nowadays technology? There were scientists trying to do that in the second half of the 20th century, and some of them bet on superconductivity. Some metals, like aluminium or lead, are not amazing electrical conductors at room temperature, but when cooled down close to the absolute zero, -273.15°C, they suddenly become the best possible one: a superconductor. Superconductivity is a so-called macroscopic quantum phenomenon, since it happens at scales much larger than the atomic one, so it was soon identified as a promising platform to try and engineer quantum effects.

We can go back to the ocean waves for a second, just to understand what is what. In this analogy, the superconductor is the ocean, and the Cooper pairs (which substitute electrons as charge carriers) are the waves. What’s missing are the rocks we are standing on: a barrier of some sort. In this case, the barrier is simply a thin insulating layer designed to stop the current from flowing in a superconducting wire, and forming a junction. Just like the rocks, the insulator does not need to be too thick or too wide, but if one hits just the right size, then quantum tunnelling can occur. How can it be measured? Similarly to what was done with light bulbs, by checking whether some particle can tunnel through the barrier and escape to the other side.

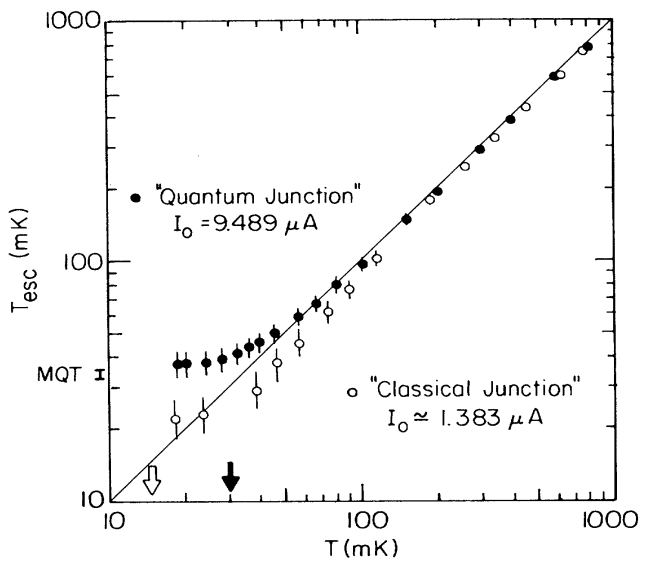

Superconductivity experiments are performed close to the absolute zero of temperature, but changing how close determines if thermal effects dominate your observations, or if quantum ones do. This is what was measured by Devoret, Martinis and Clarke in 1985, and is shown in the plot below. They saw that there were two possible regimes in their junctions: one where current was flowing through the junction with the aid of heat (straight line, labeled “classical”), and one where, below a certain temperature, heat stopped being important, as something else took over. It was quantum tunnelling. So while in the former case the lower the temperature, the lower the escape rate, in the latter one reducing the temperature was not diminishing the rate.

Beforehand I used a generic wording, “not too thick or too wide”, and dodged the numbers, but here the numbers are central. These junctions, which are the center of this and other Nobel prizes, can be several microns large. This is still a fraction of the size of a hair, but also thousands of times larger than an atom, and this is why the demonstration of macroscopic quantum tunnelling is so important. Quantum mechanics does not only live in the subatomic scale, but can be drawn on a blueprint starting from equations and ideas, can be made in a laboratory, and can be used.

There is no need to foresee the outcome of this work, as we witness it today. What in the eighties was a niche topic, a subset of a conference where only a handful of people were involved, has now grown to become one of the most active, lively, and rich research topics in physics, ranging from quantum sensing, where quantum circuits have enabled the most precise measurements ever made, to computing, which holds great promise for the future of computation. In fact, and probably not by chance, the award focused on the cornerstone of quantum technology —the physics of superconducting circuits— rather than their application, possibly leaving room for more prizes in the future.

*These might sound like intimidating terms, but there is no essential need to understand them to continue reading. The only thing that should be clear is that these are properties fixed by nature—properties that we have no handle on.