“My PhD among beetles, cacti, and icy drones”

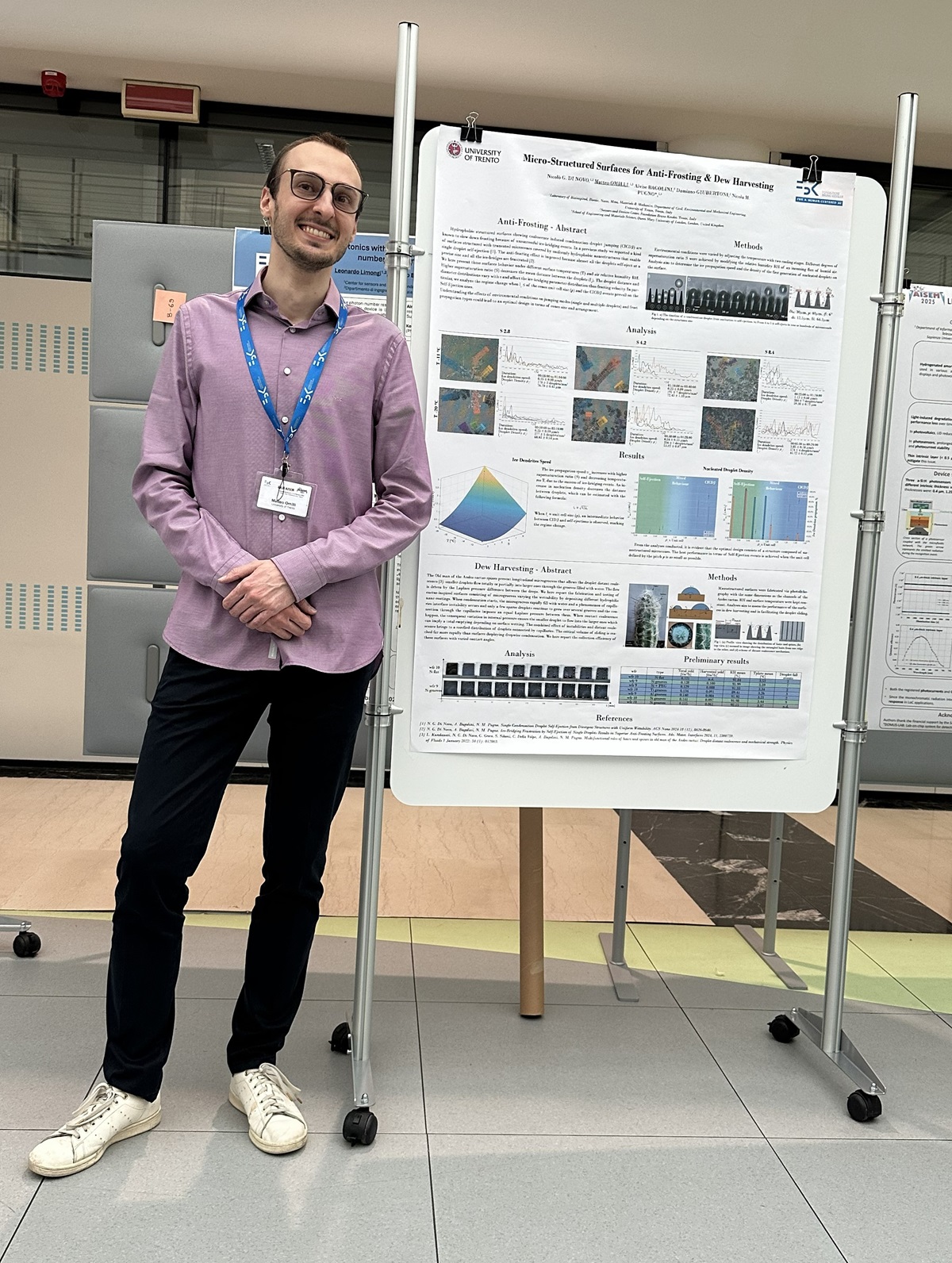

An interview with Matteo Omilli, PhD student in Space Science and Technology (University of Trento and Fondazione Bruno Kessler)

Matteo speaks calmly and thoughtfully, yet everything about him conveys a deep passion for what he does. We met Matteo Omilli, a PhD student in Space Science and Technology at the University of Trento, on a summer afternoon during his research period at Fondazione Bruno Kessler in Trento. Matteo is a young researcher with a background in architecture and engineering, a present devoted to microstructures and anti-icing surfaces, and a bright future in a fascinating branch of science called wetting.

In this interview, he tells us about his many surprising scientific projects and how they relate to space — but above all, about his vision of science as a human endeavor, inspired by nature and serving people.

- Let’s start with your research: what exactly do you do?

Imagine a drone flying at high altitude for rescue operations, perhaps in a mountain environment — cold and ice can seriously compromise its performance. My work aims to make these technologies more resilient, safe, and reliable.

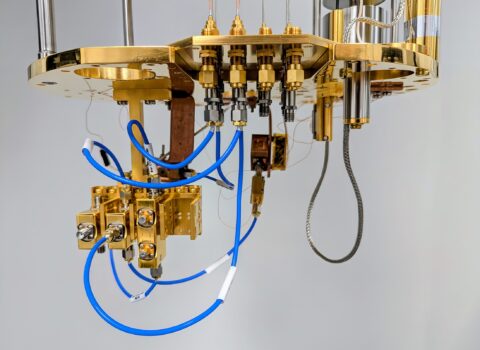

In particular, I work in the field of microstructured surfaces and anti-icing materials: at Fondazione Bruno Kessler, we are developing surfaces that slow down the formation of ice and make it easier to remove. We also collaborate with EURAC Research, where I recently completed an experimental campaign in climatic chambers capable of simulating extreme conditions — from the driest deserts to high-altitude storms.

My research falls within the study of surface wettability, i.e. the ability of a surface to interact with liquids: how much a liquid adheres, spreads, or flows across it.

These phenomena become even more complex in microgravity conditions, such as in space, where liquids don’t “fall” but aggregate in unpredictable ways.

Understanding how to control them is crucial in many space applications, from fuel management to the design of functional coatings. - A very concrete area. Where does your passion come from?

The Namib Desert beetle

It may sound strange, but it all started with a beetle from the Namibian desert. During my thesis in architectural engineering, I studied how this insect manages to survive in an extremely arid environment, capturing water from fog thanks to the shape of its exoskeleton. I designed an architectural structure inspired by it — a project that never became a physical prototype, but it taught me something fundamental: nature is an inexhaustible source of solutions, a language to be interpreted. I was deeply moved. I felt the need to delve deeper into that language — and that’s how I found my way into research.

- There’s also a second source of inspiration for your research on wetting, which comes from even more remote places, right?

Yes. I study surfaces inspired by the spines of an Andean cactus. This plant can attract and collect water droplets thanks to microscopic structures that guide the fluid: the smallest droplets move toward the larger ones until they converge toward the central body of the cactus.

It’s a microscopic but fascinating mechanism, one that can be reproduced with the advanced microstructuring technologies available at Fondazione Bruno Kessler.

The goal is to optimize water collection in extreme environments — such as deserts or zero-gravity conditions. But there are many potential applications: architecture, sensors, agriculture. Nature, if you listen to it, offers technologies refined over millions of years. - Is the SST PhD really that different from others?

Yes, absolutely. It’s a national PhD program, which means we’re spread across Italy but remain connected. Every year we meet in a different city during the SST Days, which creates real opportunities for exchange — between approaches, universities, and visions.

We also have greater resources and funding to attend conferences and work with advanced tools. But above all, we have freedom — the ability to steer our research in a personal direction. For me, that’s priceless.

Moreover, there’s no field more multidisciplinary than Space: within the program there are people working in law, astrophysics, engineering… It pushes you to explain your work clearly, even to those from completely different disciplines. It’s a great training ground for teamwork and scientific communication — both on a human and professional level. - How do you imagine your future?

I often ask myself that question. I’d like to combine my two souls — that of the architect and that of the researcher. Maybe by designing smart materials for sustainable construction, or devices for environmental management.

But even more, I’d like to be part of a close-knit team where curiosity, respect, and ethical awareness are central values. At Fondazione Bruno Kessler, I expected a very industrial and competitive environment, but instead I found people who are curious, kind, and supportive — and who truly care about their work. I’ve realized that this relational aspect is fundamental for me: everyone brings a unique experience that can enrich your own journey. I’d love to work in a group that preserves this spirit, focused on a shared scientific purpose.

In the end, what drives me is the desire to do something that’s useful to others — the desire to make a difference.

- You’ve also discovered a passion for teaching, right?

Yes! During my PhD I worked as a teaching assistant in a Building Science course. It was a fantastic experience. Seeing students understand something because of you is an indescribable feeling.

Teaching forces you to reorganize what you know so it can be shared, and that gives your path a broader meaning. Perhaps teaching is even more important than research, because it shapes the minds of tomorrow. - What advice would you give to a student who’s curious but uncertain about the future?

Don’t let doubt hold you back. Let yourself be inspired — even by something as simple as an insect or a plant. Nature has always been a source of wonder for me, and from that wonder came my choice to do research.

It’s not true that everything has already been discovered. There’s still so much to understand, improve, and invent. And anyone with passion — even those who don’t come from a “purely scientific” background — has both the right and the duty to try. - And in your opinion, what role should science play in society?

Science must be a foundational value — not only to develop technologies, but to improve quality of life. Research changes our lives, but we must ensure it does so in the right way, always putting people at the center.

We must also learn to communicate it better. Science is not just formulas: it’s passion, beauty, and a sense of the future. If we learn to share it with clarity and emotion, it can truly become everyone’s heritage.

Interview conducted by Livia Giacomini for the “Space Jobs” section of EduINAF magazine, published by INAF (National Institute for Astrophysics).