Digital skills and core competencies: an inescapable link

Roberto Ricci, President of INVALSI, was the keynote guest at the seminar organized by FBK-IRVAPP to open 2026. He presented the results of the first national survey involving nearly 500 schools across Italy

- He presented the results of the first national survey involving nearly 500 schools across Italy

Are younger generations ready to engage with the digital world critically and responsibly? What is the relationship between basic skills—such as literacy and numeracy—and digital skills? And what role do schools and educational research play, or should they play, in this area?

These were the guiding questions of the FBK-IRVAPP seminar held on January 15, which featured INVALSI Chair Roberto Ricci as a special guest. Representatives from schools in Trentino, the Department of Education and Culture of the Autonomous Province of Trento, and IPRASE also took part.

The First National Survey on Digital Skills

In his talk, Digital Skills and Basic Skills: An Inescapable Link, Ricci presented the latest INVALSI data collected from second-year high school classes during the 2024/2025 school year, as part of Italy’s first national survey on digital skills.

The survey comes against a backdrop of relative stability in the Italian education system over recent years: the share of students who fail to reach basic proficiency levels in Italian and mathematics remains high, with no significant recovery compared to the pre-COVID period.

The digital skills survey involved nearly 500 schools nationwide and was based on online assessments with authentic tasks, aligned with the European Commission’s DIGCOMP 2.2 framework. DIGCOMP defines the skills needed to: (i) assess and understand online information (information and data literacy); (ii) communicate effectively, share resources, and manage digital relationships (communication and collaboration); (iii) create and rework digital content; (iv) protect privacy and personal well-being (security); and (v) understand digital systems and solve problems in everyday online contexts. The INVALSI survey covered four of these five areas.

Strong overall results, but not for everyone

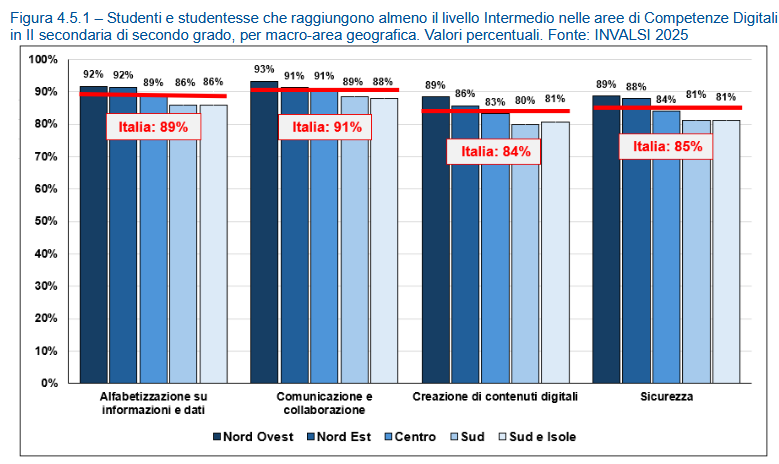

Compared with basic skills, the overall picture for digital skills is more encouraging. At the national level (see figure), more than four out of five students achieve at least an intermediate level: 89% in information and data literacy, 91% in communication and collaboration, 84% in digital content creation, and 85% in security.

Local differences do exist, as shown in the figure, and partly reflect familiar patterns, but they are not especially pronounced. Factors such as specialization of high school (partly determined by school selected at the end of middle school) and students’ socio-cultural background are more influential. Gender shows mixed associations—positive in some areas, such as communication and collaboration, and negative in others, such as security.

Local differences do exist, as shown in the figure, and partly reflect familiar patterns, but they are not especially pronounced. Factors such as specialization of high school (partly determined by school selected at the end of middle school) and students’ socio-cultural background are more influential. Gender shows mixed associations—positive in some areas, such as communication and collaboration, and negative in others, such as security.

One key finding concerns the relationship between basic and digital skills: although they are distinct, they develop together. Students who perform better in Italian and mathematics also tend to have stronger digital skills. According to Ricci, this should discourage the idea that the two sets of skills are alternatives to one another.

Open questions

The survey holds significant potential for future development. Unlike other international assessments, it could be extended to all school levels, offering a detailed national map of digital skills.

Despite the generally positive results, several issues remain unresolved. Area, school, and family contexts continue to influence digital competence, pointing to a form of educational poverty that research institutions and policymakers must tackle together through targeted and effective interventions.

Personal safety and well-being related to digital device use is another area of concern. While students generally show awareness of online risks, only four out of ten reach an advanced level of competence in this domain, making careful monitoring essential.

Artificial intelligence also enters the picture. According to Ricci, schools still tend to take a defensive stance, focusing on control and fears of cheating. The real challenge is to change perspective and treat AI as an object of assessment, not merely a risk.

Finally, there is the risk of emphasizing digital skills as a way to sidestep the challenge of strengthening core competencies. As Ricci stressed, digital skills cannot replace basic ones; they can only complement them. This brings teachers and schools back to the center of the discussion, often overburdened and left to cope on their own. Guidelines alone are not enough—schools need concrete support, training, and ongoing guidance. Research has a crucial role to play here as well, by producing evidence that informs not only educational policy but also everyday classroom practice. This requires not just data, but stronger dialogue among the social sciences, especially between quantitative approaches and qualitative fields such as pedagogy.