History changes

Massimo Rospocher is the new director of the Italian-German Historical Institute FBK. We asked him about his plans for the coming years, how history is changing and how his own history has changed.

A ‘returning’ Trentino, in the sense that his academic career is a circle that started and ended (for now) in Trento, Massimo Rospocher has been the new director of the Italian-German Historical Institute of the Fondazione Bruno Kessler since the beginning of this month, following the end of Christoph Cornelissen’s term of office.

A graduate in Literature and Philosophy from the University of Trento, he holds a Master’s degree and a PhD from the European University Institute (EUI) in Florence, and has held various fellowships at international institutions in Europe, the United States, Canada and Australia. These include the British Academy, Warwick University, Yale University, McGill University, CRRS Toronto, University of Melbourne, University of Sydney.

He returned to Trento with a three-year post-doctoral position at the Italian-German Historical Institute between 2007 and 2010, before becoming a full-time researcher at ISIG. He taught at the University of Leeds for four years (2011-2015) and returned to FBK in 2015. Since then he has coordinated regional and international research projects, including the PUblic REnaissance project (https://hiddencities.eu/) funded by the HERANET consortium.

As a historian of the culture and society of early modern Europe, his research revolves around topics as diverse as: the history of public opinion and propaganda; the study of media power, communication and information; the history of European cities; and the methodology of historical research. He has published books and essays in Italian, English, German and Spanish, focusing on leaders such as the ” warrior pope” Julius II and anonymous street performers, Renaissance humanists such as Erasmus of Rotterdam and itinerant pedlars.

We asked him about his plans for the institute, how the practice of history is changing and how his own has changed.

– From FBK-ISIG researcher to director of the Institute itself, what did you think when you received the official news of your appointment?

My thoughts went back to a few years ago, when we were about to move to Australia with the family in the summer of 2019. My wife had a great job offer in her hometown of Melbourne and we were determined to move down under. We changed our minds at the last minute, on the ferry back from Sardinia. Without much certainty, to be honest. When you make decisions in life, you are never sure you have made the right one. I’d say it was worth it.

– What are your plans for the Institute in the coming years?

Over the last few decades, the scientific and historiographical frameworks, the political and institutional contexts, the funding mechanisms and the world of research in general, as well as the methods and languages used to disseminate history and other sciences, have changed rapidly. In this changing and sometimes confusing context, the ISIG must not forget its roots, its tradition and its original mission, but must project itself into the future, adapting to new trends and the ways in which historical research is conducted, supported and communicated.

From a research point of view, therefore, there will be elements of continuity and innovation. First of all, the ISIG cannot forget one of the reasons for its foundation, namely to act as a “post station”, as one of its founders defined it, between the Italian and Germanic scientific worlds. For the sake of continuity, we will continue with the line of research dedicated to the impact of media and communication on societies of the present and the past, a field of research that has marked the course of my predecessor and that has positioned the ISIG on the international scientific scene.

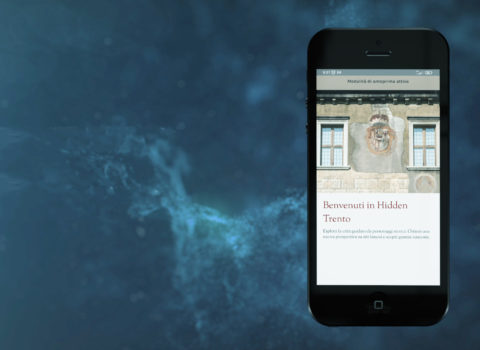

We will also explore new areas such as environmental history, the study of mobility or digital and public history. We will also try to invest in the languages with which history is communicated to a wide audience, not just an academic one. One example that concerns me is the Hiddencities family of apps for smartphones, developed as part of the European PURE project that I coordinated, which uses new technologies to try to offer an immersive experience in the cities of the past, translating the results of research into an understandable language.

– Will there be initiatives and events for a general audience?

2023 will be the half-century anniversary of ISIG. Founded in 1973, ISIG was the first research centre created within the former ITC. We are therefore planning to use the occasion of the 50th anniversary for a series of events, both scientific and for a general audience.

From a scholarly point of view, the highlight of 2023 will be the 64th Study Week in December, which will be an opportunity to celebrate ISIG’s half-century of history with some of the world’s leading historians. The theme will be a reflection on the major ‘turning points’ that have dominated historical research since the new millennium: environment and climate, media and the digital, gender and emotions, mobility and globalisation. An attempt will be made to answer a fundamental question: is this constant change an indication of the vitality of history or a sign of the discipline’s crisis? I believe that this is a reflection that concerns not only history, but more broadly all the humanities and social sciences.

In 2023, the Paolo Prodi Prize will be awarded again, a prize dedicated to the founder of ISIG and aimed at the best literary work on a historical theme published in the last two years. The award ceremony will be linked to a public event aimed at citizens.

– What can be the role of historians in our society in general?

If I had to answer the question of the role of history in today’s world, I would have to say that it has lost its public and political function. One of the reasons why history has become quite marginal in the public debate is that historians (not all of them, of course) have lost the ability to narrate and communicate, outsourcing this function to other figures. I believe that historians need to reclaim this public role.

To regain a central place in the public debate, historians should be able to project onto the past the questions that arise from the urgencies of the present, without falling into presentism or ignoring anachronism. History does not repeat itself, but our inevitably anachronistic questions do not negate the value of the answers that come to us from the past.

– In the context of FBK, a discussion of links with other research centres

Beyond the obvious connections with the humanities centres of the FBK, there are issues that ISIG and historians in general have been working on for some time, and which weave together many of the themes addressed in the other centres. These include heritage, digital culture and technological innovation, information and fake news, and the environment. The pandemic, for example, has sharpened the widespread perception that we are living in a moment of radical change for humanity, and in this sense, looking to the past has served not so much to predict the future as to put a collective experience into perspective. The same can be said of the debate about the digital revolution we are currently experiencing, a pervasive rhetoric reminiscent of other moments in history when the sudden arrival of a new technology has disrupted societies in the past.

Then there is a more operational dimension. The profession of historian has always been an individual, almost solitary one. My impression is that, for a variety of reasons (large international projects, interdisciplinary approaches, etc.), the way historians work is becoming increasingly collaborative and more akin to the laboratory dynamic that characterises other FBK centres.

– Speaking of your own history, what did you dream of doing as a child? At what point in your career did you decide to do research?

History is an interest that matured in adulthood, while my great passion since childhood has been sport. I was therefore fascinated by professions such as sports journalist or coach. However, according to my professors, I was particularly gifted in mathematics. In short, it didn’t all go according to plan.

– What advice would you give to young people considering a career in research?

I think that everyone should be driven by their own curiosity, without which they would not accept the sacrifices that an often precarious life imposes on those who want to make research their profession. To be honest, it really takes a lot of passion and self-denial to want to go down the path of research in Italy, especially for those who do not come from a privileged background.

For my part, I would also advise everyone to gain experience abroad. Apart from the real problems that cause many people to leave a country like Italy, I have always been puzzled by the rhetoric of the brain drain; working, living, studying in contexts other than one’s own, as well as a form of enrichment, will increasingly become the norm in our society.