In conversation with the world

The new issue of A.R.O. features a rich selection of reviews, including volumes on the Red Brigades, the legacy of fascism, the mobility paradigm, and bibliophile stories. There is more: the magazine covers many other books, spanning different places and eras. We invite you to discover how reading history can create proximity and maintain a constant dialogue with the world, despite distances.

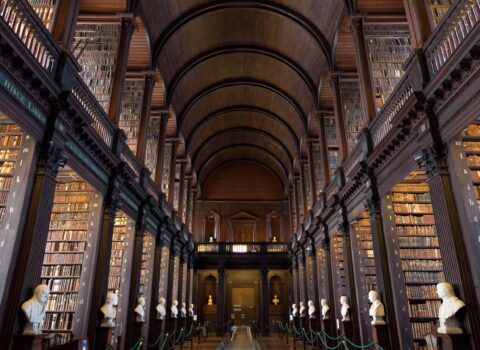

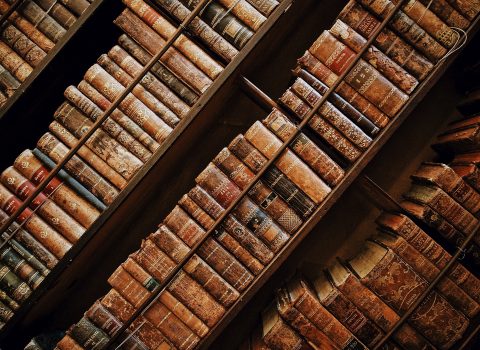

“Those who have a book with them are never alone,” one of my high school teachers used to repeat constantly. Whether he said it to encourage us to cultivate this beautiful habit – i.e. carrying with us the words written by others – or out of some stereotype, it does not matter: since then, this phrase has occupied every remote corner of my mind and often reminds me of her presence with a faint echo. A bit like the books at the bottom of the shelf, the protagonists of one of the pieces featured in the latest issue of Annali. Recensioni. Online, the open-access journal of the Italian-German Historical Institute. It is a collection of essays exploring the stories of bibliophiles and book collections in Trentino, originating from the 2020 teleconference of the same name. In that suspended year, the region’s conservation libraries managed – albeit only virtually – to show the public part of their literary heritage, as if to remind us that even in moments of distance, a book can continue to foster connection. The title, At the Bottom of the Shelf, suggests something forgotten or of little interest. Yet, as Vanessa Rossi writes in her review, recalling the conclusion of the volume, “[…] what lies at the bottom is also what underlies what lies above.”

The book – edited by Matteo Fadini, Italo Franceschini, and Mauro Hausbergher, with the collaboration of Laura Bragagna – is just one of the seven works featured in the “Various Eras” section, followed by five in “Modern History” and, finally, twelve in “Contemporary History.” Among the latter, the collection of essays edited by Carmen Belmonte and reviewed by Giulia Grechi on the survival of the fascist era in art and architecture caught my attention – probably because of the ongoing debates in our country. It attempts to answer complex and urgent questions (How do we live immersed in the material and immaterial traces of fascism? What do those traces tell us about who we are today and who we want to be in the future? Who has the right to take the lead in this process of re-narration and critical reuse?) It serves as an invitation to build a more conscious, critical, and democratic relationship with that memory.

Finally, as proof that within the pages of a book one can find not only company but also answers (how much triviality hides in rhetoric!), one only needs to read the first lines of the review of Connected Mobilities in the Early Modern World. The Practice and Experience of Movement. In the opening anecdote, reviewer Luca Zenobi recounts how a colleague once asked why the topic of mobility aroused such interest among historians—and how he struggled to find a fully convincing answer. Today, however, he would simply say: read Connected Mobilities, a book that clearly shows how the study of mobility can become a key to understanding the world and the relationships between people.

Last in this review, but first – as always – among the A.R.O. features, is the Forum book, the section where the review is entrusted to two distinct voices. In the latest issue, the spotlight falls on Dolore e furore (Pain and Fury, Translator’s note) by Sergio Luzzatto. As noted in the editorial, this choice aims to give space to an important book while also “bringing to the center two emotions that historical research constantly encounters: pain and anger. Feelings that are not confined to individual experience, but become part of collective memory, political struggles, social processes that mark the ages».

Perhaps, then, my teacher was right and not because the pages simply fill the silence. It is rather through the voices that inhabit books – those of authors, curators, reviewers, and readers who “walk” through them – that we learn to hold together times and places, memories and movements. And perhaps this is precisely the meaning of reading: to stay in conversation with the world – even when, for a moment, we seem to be outside it.