The Magic of Physics: Nobel Prize Winner Ketterle Charms the Muse Science Museum

The German physicist was the protagonist of the closing event of Researchers' Night 2017

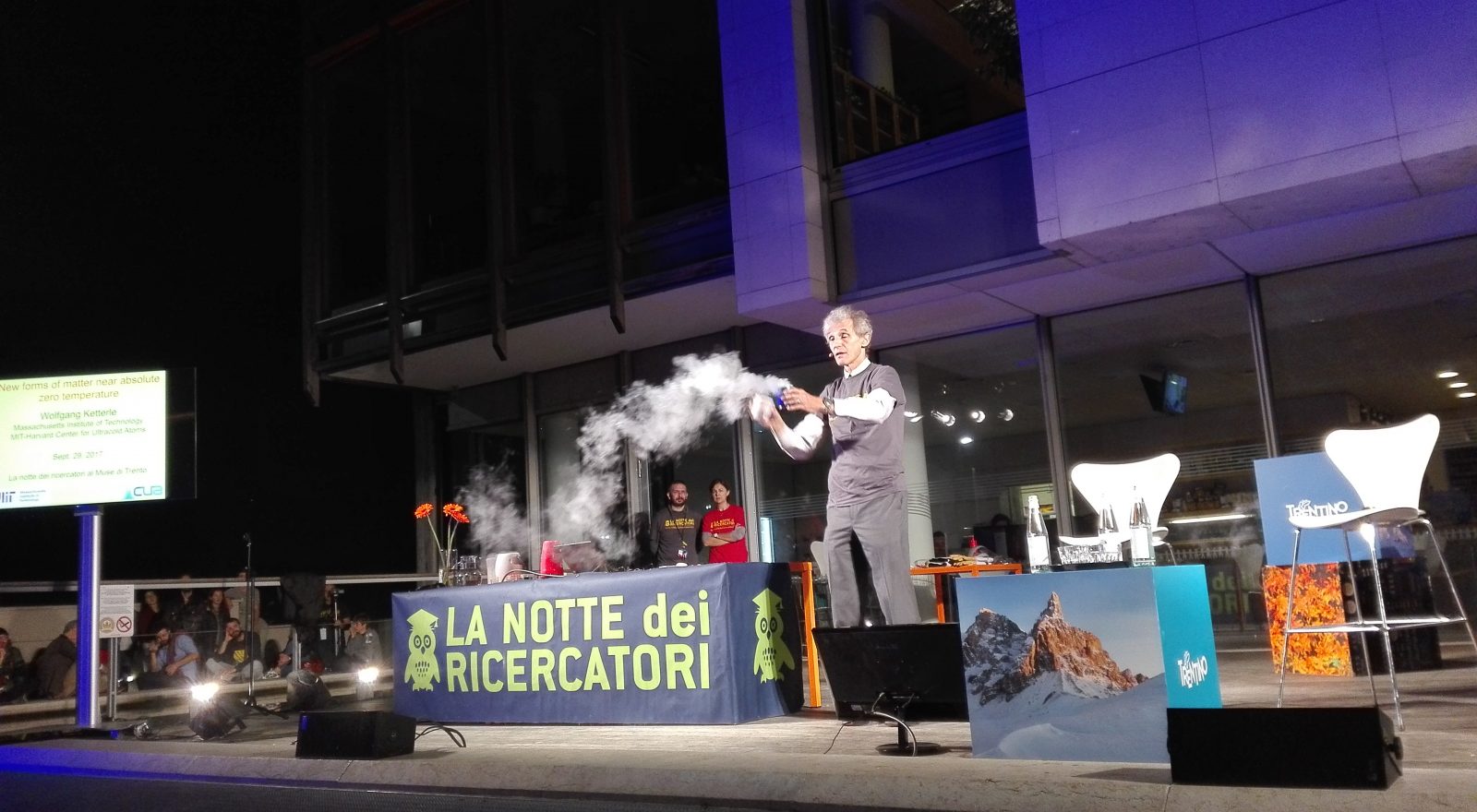

If you cool matter at extremely low temperatures very strange things happen: for example, a banana or a flower can become dangerous blunt weapons, and objects levitate. Magic? No, just physics: Nobel Prize laureate Wolfgang Ketterle proved it during the spectacular evening event that closed the rich program of Researchers’ Night, on stage at Muse on September 29.

Ketterle, armed with liquid nitrogen and contagious enthusiasm, charmed the audience from the terrace of the Muse Cafè with some live experiments, all perfectly successful: with a simple “dive” at temperatures close to absolute zero (the lowest limit beyond which it is impossible to cool an object, equal to -273 degrees Celsius), soft objects turn into marble, balloons deflate and, thanks to superconductivity, it is also possible to induce levitation in a piece of pottery.

Ketterle is “in his element” at these temperatures: in 1995 a research group led by him at MIT Boston was among the first ones to experimentally produce the so-called “Bose-Einstein condensate“, a particular state of matter that is created in extreme conditions, at very low temperatures. A measurement pursued for 70 years, and that everyone doubted could ever be achieved. “When I realized I had done that observation in the lab, it was an ecstatic, unforgettable moment, ” Ketterle recalled on the stage, almost nostalgically. Also because that experiment won him the 2001 Nobel Prize for Physics, shared with colleagues Eric Allin Cornell and Carl Edwin Wieman.

After the experiments, Ketterle answered questions from Marco Motta, scientific journalist of Radio3 Scienza and moderator of the event, and from the audience (received through text messages). A more intimate portrait of the German physicist was revealed, when he recalled some of the steps that led him to become a scientist. “I was a very good student at school and at the university,” he admitted without false modesty, but paid the right tribute to his mentor David Pritchard, whom he defined as the “most influential person” in his life, and to whom he gave his Nobel Prize medal.

He also gave advice to the many young people present among the public, especially those who are starting their careers in research. “Doing research with passion means living an exciting and extraordinary life, but you must be prepared to make sacrifices and even to compete.” In this regard, the physicist recalled the friendly “rivalry” with the scientists with whom he later shared the Nobel Prize: “Scientific research often works like sports: You may know your opponents well and “train” with them, working together, but in the end you want to win. ” If a marathoner ( Ketterle has run the marathon in Boston and has a personal record of 2:44:06) says so, you have to believe it.