Archives and research: the conclusion of the Grenzakten 2.0 project

Archival study and the evolving concept of borders at the heart of the Grenzakten 2.0 project, thanks to which the large documentary collection on the borders of modern Europe preserved in the two State Archives of Innsbruck and Trento is now accessible.

The Grenzakten 2.0 project was recently concluded, during which an Isig research team examined various documents on boundary deeds (Grenzakten) dated between the 16th century and 1854. The main purpose of the project was to examine and compile an online inventory of documents related to the Venetian-imperial border today divided between Italy and Austria. Even before the signing of the peace treaty of Saint Germain en Laye in September 1919, this documentation was divided following the principle of archival relevance, rather than that of origin, which was then set as the criterion for the subdivision of archival fonds and for the deliveries of materials to the successor states of the former Habsburg monarchy, which included Italy. This action gave rise to an anomaly represented by the splitting of a coherent collection into two separate groups of records, as happened, moreover, also during the massive document transfers of the Napoleonic era.

We asked historian Katia Occhi from FBK-ISIG, curator of the project, to tell us about the phases and peculiar aspects of the project.

What does it mean to work on archives?

Thanks to the suggestions offered by studies inspired by the so-called archival turn, in recent years historians, anthropologists and archivists have started studying the cultural history of archives. They no longer analyze archives in the traditional way, as a source or raw material data, but as a constructed cultural object: it has become a monument (in the etymological sense of the term) of what is remembered and a testimony to state power as a producer of facts and classifications.

This has shifted the focus from the properties and characteristics of the document to the path that leads documentation to become archives. From this perspective, it is incumbent on historians to decipher not only what the document says, but the intention lying behind its production and preservation, why it found that location in that given place, and when that occurred.

These suggestions have in part also inspired the research I (Katia Occhi, ed.) recently conducted on the physiognomy of the archives of the ecclesiastical principality of Trento, suppressed in 1803, and to investigate the specificity of the materials preserved today in Trento, deeply marked by the dispersions that occurred at the beginning of the nineteenth century, when the oldest part of the bishop’s archives was taken from the staff serving at the Gubernialarchiv in Innsbruck, to be concentrated in the central archives of Tyrol, while an important portion was transferred to Vienna and one to Munich.

Studying how past societies managed their archives allows us to shed light on what consequences these choices had on our historical knowledge. The deep lacerations that troubled Trentino and Tyrolean history in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries were reflected without fail in the documentary heritage, and this has not always allowed a full understanding of the past of an area whose political, economic and social physiognomy was profoundly marked by the integration of the Latin and German worlds and of mountains and plains. Today it is clear that areas of intersection such as Trentino and South Tyrol must be examined in all the archives that can account for them, and this is particularly important for this reality, whose archives have long been preserved and reordered beyond the Alps, as we have been able to ascertain with this research.

What, in particular, did the Grenzakten 2.0 project deal with?

The project, co-funded by Caritro and conducted through two archival calls, examined sections “IV. Tirol gegen Venedig” and “V. Tirol gegen Trient” (bundles 43-56), a collection divided today between the State Archives in Trento, where it arrived at the end of World War I, and the second that is preserved at the Tiroler Landesarchiv in Innsbruck. Research has shown that it collects documents attributable for the most part to the diplomatic activities of the commissions that worked to settle border disputes between the Habsburg monarchy in the Tyrol area and Bavaria, Salzburg, Venice, Trento and the Grisons. In the first tranche of work, deeds pertinent to Trentino included between 1452-1912 were indexed and an inventory was compiled, which is now available online.

The second tranche of the project allowed for the filing of border-related documents held at the Tiroler Landesarchiv in Innsbruck, covering the areas towards Val Pusteria, Cadore, Marmolada and the valleys of Non and Sole, bordering the ecclesiastical principality of Trento.

These are materials from the eighteenth century: correspondence, memorials, proclamations, protests, reports of the Venetian rectors and imperial ambassadors to Venice concerning disputes between the states. These are information-rich materials that highlight military problems on the one hand, but also refer to the competitive exploitation of resources at the basis of the mountain economy.

What was the historical importance of the border?

As mentioned, the documentation is very heterogeneous, on the one hand it photographs the situation of a border that is a zone of passage, which ran along strategic areas, which have always been political, ecclesiastical or cultural border zones. Barrier and border, yes, but at the same time permeable and porous places, where for centuries different languages and traditions have combined. The intertwining of interests, ways of discussing, and hostilities that arose from being on the frontier involved advantages and risks, changing according to circumstances and convenience.

Behind the border conflicts negotiated by international diplomatic representatives lay a series of economic dynamics. The documented reality for these villages located on the borders between two international powers such as the Venetian Republic and the Empire shows that this was not a closed society, but a reality embedded in a circuit of exchange and reciprocity, in which the mountains of the old regime were linked to the lowland economy, particularly that of the Veneto region, whose capital was one of the largest European cities in the early 16th century.

So living along the border did not always highlight disputes and contrasts, in some cases we are faced with the sharing of resources between villages on this side and on the other side of the border line. In the case of the pastures at the foot of the Pale di San Martino in Primiero, for example, we can see that in addition to the local communities there were parishes in the Feltre district that owned large pastures in the valley, which they rented to foreign families of Feltre or Trevisan nobles, from which they earned income in money and cheese.

It was strategic for mountain people to have access to the resources of forests and pastures, which enabled them to cope with the scarcity of income from the few agricultural lands. Entering resources such as timber and, in some cases, minerals into urban markets made it possible to cope with the shortages of the subsistence economy and to have the liquidity to purchase foodstuffs and miscellaneous goods. Therefore securing possession of these assets was crucial.

How has the concept of the boundary changed over time?

To answer this question we need to let the documents speak for themselves. The documents we filed during the project were collected in the second half of the 18th century for the diplomatic activities of the Austrian border commissioners, and once their usefulness ceased, they were concentrated by the Gubernium in Innsbruck into a single collection, where in the early 20th century they were reorganized under the name Ältere Grenzakten.

The activities of the commissions were part of the administrative, judicial and iscal reorganization policies of the Habsburg monarchy that began in the 1840s and continued thereafter. They led to a general reorganization of administrative jurisdictions and the regulation of boundary lines. During the second half of the eighteenth century, numerous agreements were signed between the Venetian Republic and the Habsburg monarchy, with extraordinary commissioners in charge of the borders, which extended from Istria to Mantua. A precise definition was pursued based on ancient possession and unchallenged customs. This led to bilateral treaties that minutely regulated every possible dispute by defining the terms of their respective sovereignty with a precise line that followed natural boundaries, ideal lines that proceeded along mountain ridges or the course of rivers (where possible). These demarcation lines would eventually form the Austro-Italian front until the Great War.

The apparatus of international diplomacy alternated in a series of official talks and private negotiations, in a mixture of confidential meetings and rigid ceremonial.

The boundary-setting process was the result of negotiations at various levels and concrete acts and involved a variety of actors and interests. In order to prove village titles to forests, pastures, and sheperd’s cottages, villages had to submit legal titles. When there were no documents, recourse was made to the memory of the older inhabitants, who were assigned the task of passing on the knowledge that ensured the community’s benefitting from common property (pastures and forests). These were called upon to lay on the location of boundary stones, usually stones engraved with crosses, or if the boundary ran in the bed of a river or near a boulder. When memory did not go so far back in time, they proceeded in this way: “in antique things exceeding the memory of men, it is sufficient that witnesses say that they have heard by fame what the true boundaries of a place were…“.

What, then, was the end result of the project and how can the data collected be used?

Thanks to digital tools and computerized filing, it was possible to virtually heal the fracture of section “IV. Tyrol gegen Venedig” of the “Ältere Grenzakten”. The public now has an access tool to the large documentary collection on the borders of early modern Europe preserved in the two State Archives in Innsbruck and Trento. It constitutes a relevant building block for the reconstruction of the history of international relations between the Venetian republic and the Habsburg monarchy. This material, almost unknown until recently, is made available to the public and to specialists thanks to the two new online inventories from which one can begin a path of in-depth study for degree and doctoral theses both in Italy and in Austria, particularly for those interested in the history of the border territories with the Alt Tirol.

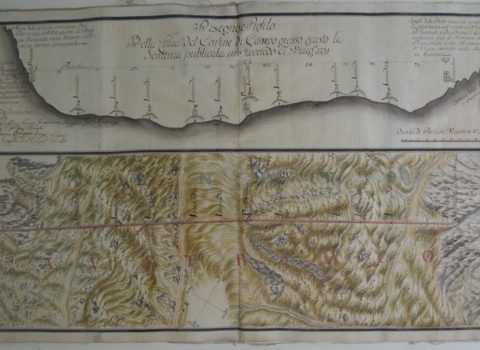

State Archives of Trento, Boundary Acts, Series I, b. 16, 2, The so-called Pietra favella marked the border between the Empire and Republic of Venice at Pian della Fugazze, year 1751

Cover image: State Archives of Trento, Boundary Acts, Series II, Primiero, Fiemme, Fassa, b. 36, 1842-1911, plan for the galleries of the Vallalta, Mis and Sagron mines.