Let’s start at the end: the footage of Kessler’s funeral

Thanks to a VHS, we can review the original 1991 footage, which allows us to reflect on the fact that the images we see are always the product of someone's choice.

Documents in an archive are not always just letters, but can be photographs, diaries, and even audiovisual products. All these sources are important for reconstructing the past, but images tend to be riskier because we are less accustomed to questioning their veracity. However, they too are the product of an option. Someone chose to capture them at a specific instant and from a particular angle. They did so for a number of reasons that are important to investigate if we really want to understand the story we are trying to tell.

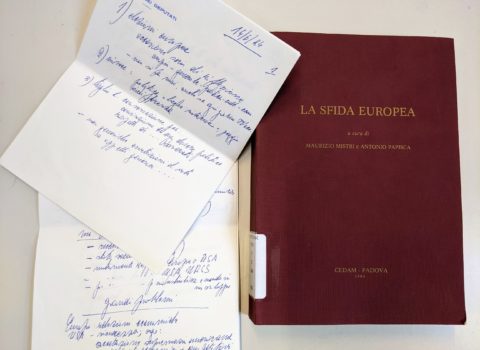

The Bruno Kessler Private Fund, kept at the Provincial Archives of Trento, contains 43.5 linear meters of documents – a stack as tall as the Trento Civic Tower, to be clear. One of the first documents I looked at was precisely an old VHS. I arrived at the archive, put on my headphones (so as not to disturb anyone) and started watching.

It is March 22, 1991. A car is proceeding in the rain on the roads of Val di Sole, inside it a cameraman is filming the journey. When he sees the sign for the village of Mezzana, he asks the driver to stop the windshield wipers, only then can he shoot that part without too many interruptions. This sounds trivial, and perhaps it is. However, it also makes us realize that the videos we see are constructed to the smallest detail. For the development of the narrative, Mezzana is important. Perhaps it is because the village has seen a significant increase in tourism thanks to the new Marilleva train station, provided for in the Provincial Urban Plan developed at Bruno Kessler’s will at the time he was president of the Trento Province.

Framing that precise moment serves the purpose of showing to the viewers’ eyes Kessler’s last trip to his beloved Val di Sole. Bruno Kessler had died on March 19. The funeral mass and burial took place in Vermiglio, the town to which his family had moved after the untimely death of his father. A solemn funeral had been held in Trento’s Cathedral Square on March 21. From the mortuary set up in Depero Hall, in that same hall where Kessler had been a key player in the provincial council as president, a long procession had followed the coffin to the heart of the city of Trento. (video from minute 4:26)

Many, however, were waiting for him in Piazza Duomo, among them loro Silvius Magnago. Magnago had been the president of the Südtiroler Volkspartei, the majority party in South Tyrol, and president of the Province of Bolzano) for 30 years (from 1960 to 1989). He was the face of autonomy in South Tyrol. His actions had been instrumental both in the approval of the so-called Package – the set of regulations drawn up by Italy and Austria to protect the South Tyrolean minority – and in its implementation with the Second Statute of Autonomy. His presence had a potentially emotional impact because he was a war amputee (he had lost a leg on the Russian front fighting for Germany), was ten years older than Kessler, and in 1991 had only recently left the leadership of the Province.

Once again, however, the protagonists of this story of ours, which is possible thanks to raw footage preserved in the provincial archives, are the operators. When the video takes us to Piazza Duomo, one of them exclaims,in Trentino dialect, “Go Martino, there’s Magnago, it’s a fantastic image.” Journalist Alberto Folgheraiter also told me how that very image had stuck with him: Magnago, by then old, sitting under the black catafalque waiting for the procession. He would have taken that photograph today, he says. At that time, in the packed square they had failed to capture the image in all its power. One is left to wonder what that photograph that does not exist would have told them then and what it would tell us today.