“AI & History”

A series of seminars to reflect on how artificial intelligence is revolutionizing the way History is made.

Like all stories worth telling, History is also made up of twists that inexorably change its course. Historians call them caesuras (i.e. disruptions ed.), because they mark an irretrievable break between the before and after. It is good historical practice to assess only with hindsight the actual impact of a caesura, although in some cases, it is the historians themselves who are overwhelmed, along with the entire society of which they are a part, by twists and turns that, even before History, condition the “everydayness” of the present. For yes, the ongoing digital revolution and the unstoppable spread of artificial intelligence – which is now within reach of smartphones – are revolutionizing even what, at least at first glance, may seem one of the most fossilized scientific disciplines.

The time to make a historiographical check on the impact of this digital revolution is therefore, at least for now, has come. Nevertheless, a brief look at the media revolutions that have marked the course of History is enough to suggest (even to historians) that it is better not to be caught unprepared. Rather, the invitation is to take an active part in the development and use of artificial intelligence, which, consistently, is also changing the way we make History.

The international seminar series “AI & History,” which started on Feb. 3 and will keep us company with four more meetings in the coming months, aims to reflect precisely on the new horizons of work that artificial intelligence proposes to the historiography of the 21st century. The aim is to present working tools based on the use of artificial intelligence, experiences and research perspectives, but also reflections and theoretical problematizations at the historiographical level.

A main issue, which Marnie Hughes-Warrington (University of South Australia) will reflect on in the next meeting, which will be held online on March 17, is to ensure safe and reliable parameters in historiographical reconstructions by artificial intelligence. The problem of historical objectivity of artificial intelligence, on the other hand, will be addressed by Jo Guldi (Emory University), who will close the series in June. Instead, both theoretical problems and practical reflections will be the focus of the May 12 seminar by Federico Mazzini (University of Padua), who will talk about the challenges of the potential creation of a chatbot assistant for historical research. Another talk dedicated to the practical dimension will be the one by Drew Thomas (University College Dublin) who, on April 29, will present his research project based on the use of artificial intelligence in the analysis of visual sources.

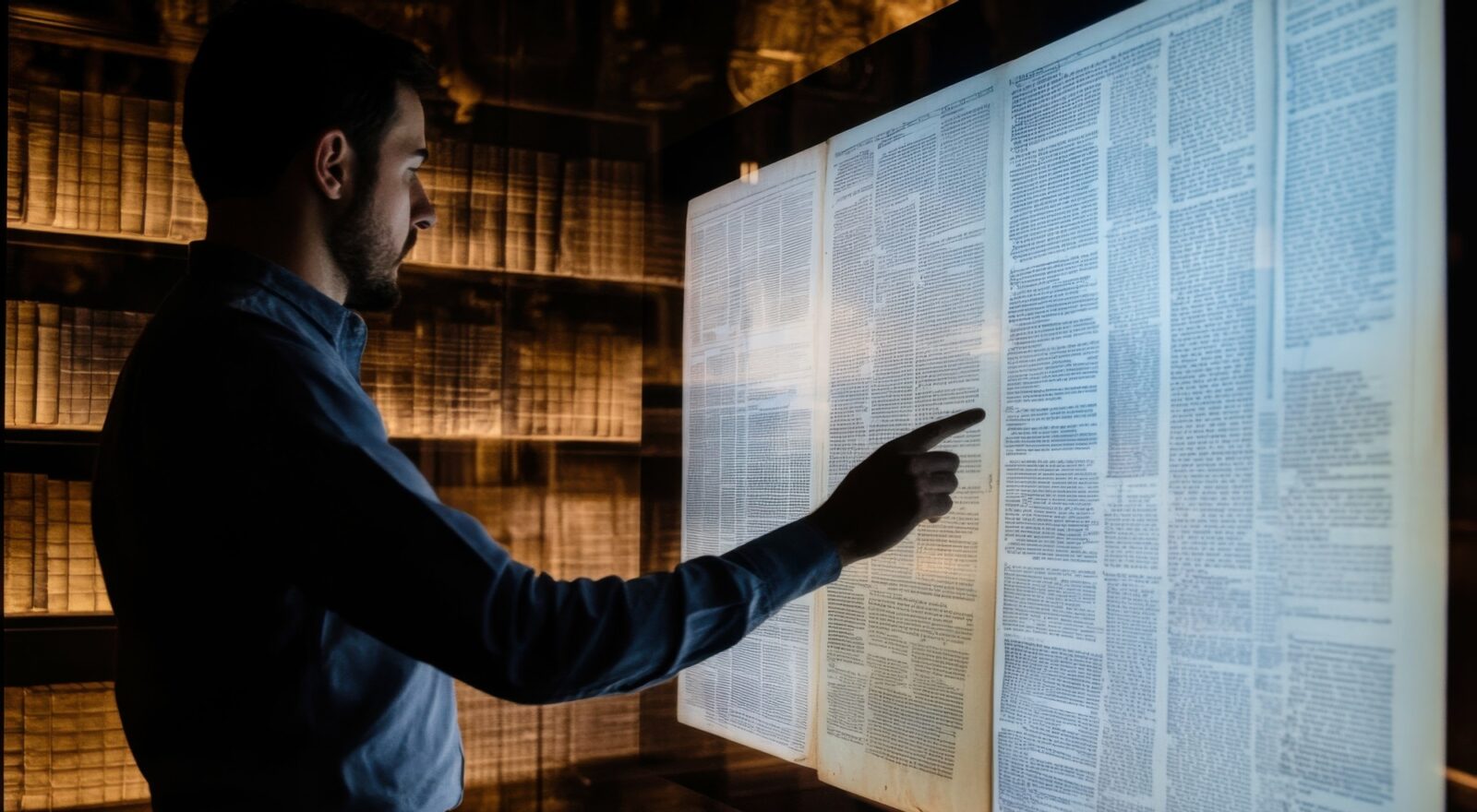

An early anticipation with respect to the scope of this digital revolution has already emerged from the first meeting of the series where Andy Stauder, managing director of READ-COOP SCE, presented the Transkribus transcription software. This is an application that is disrupting perhaps the most ingrained and indispensable practice of the historian’s work: the research, study and analysis of unpublished archival material. Exercising endless patience, generations and generations of historians have burrowed their way through piles of bound papers covered in the dust of centuries in sometimes forgotten or inaccessible archives. They have turned over folders, untied files, flipped through pages and pages of manuscripts, copying in pencil texts written in the most absurd and indecipherable (paleo)handwritings.

The promise, but also the gamble, of Transkribus lies precisely in subverting this data collection process through the use of artificial intelligence. One just uploads images of the manuscript to the platform, selects a suitable transcription template, and that’s it: artificial intelligence recognizes the various text boxes, lines, and, of course, individual words and letters, giving an often near-perfect transcription. Within a few years, the algorithm has managed to achieve a near-zero error rate in reading the hostile Gothic handwritings that have been the nightmare of entire generations of young researchers. It is no coincidence that it is from Austria and the German-speaking world that Transkribus has managed to find a now global diffusion, becoming the software of choice for numerous projects borne by major cultural institutions.

For insiders, Transkribus is not new for sure. The creation and availability of transcription software is far from an invention or a prerogative of READ-COOP SCE. The popularity of Transkribus, however, probably lies in one of those characteristics that, as History teaches us, fuel big media revolutions: first, a user-friendly interface; second, the ability to reach a wide audience, not only experts; and, finally, the flexibility to adapt to countless different contexts, i.e., the unrepeatable uniqueness of any manuscript. In short, to use Transkribus successfully, one does not need to be a computer scientist, one just needs to be a historian.

The program for the ‘AI and History’ series can be found here: https://isig.fbk.eu/it/ai-and-history/. All the series conferences are open to the public, both in-person and online.