Hotspot hemisphere

Legal ambiguity of the European migration governance

Genesis

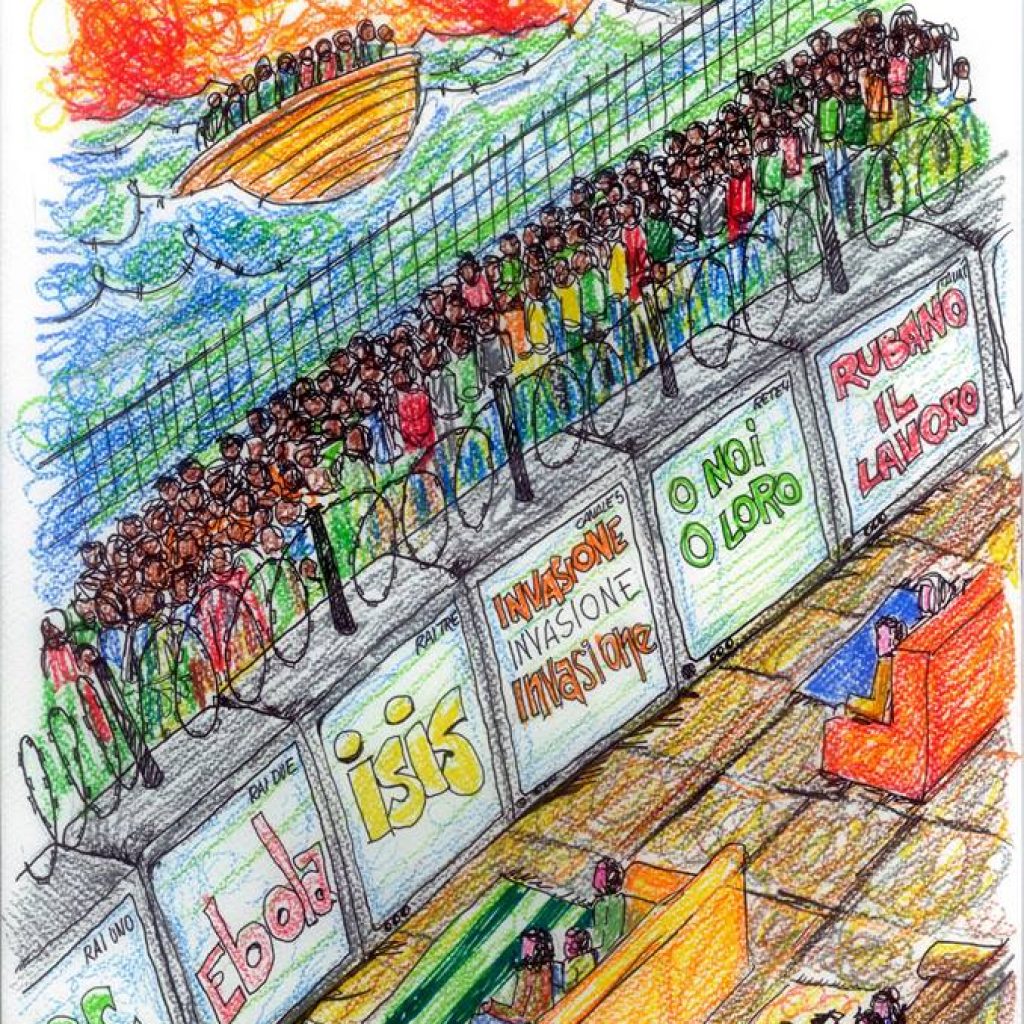

Spring 2015. The national debate about the migrant question is getting more and more inflamed, and the positions, apart from the sectors of society that struggle to have their voice heard, are polarized between the one of the extreme right, that incites violence, and the rigid technicalism of the European institutions, echoing in the centrist and “moderate” governments of the various member countries. In this continuum of positions, the difference seems to lie much more in form than in substance.

Migratory trajectories are always hindered, to the south, by a Mediterranean sea that increasingly resembles a cemetery, and to the east by various political boundaries guarded by the police and military forces of various countries. The internal movements of Europe, the so-called “secondary movements” are still hindered by the Dublin Regulation, which, based on the fingerprints collected in the first landing site, assigns responsibility for the individual asylum application to that country, thanks to a European fingerprint storage computer system (EURODAC). Southern European countries are the main buffer to migratory flows, a bit wall and a bit filter for that docile labor force that is convenient to the countries of central and northern Europe in small waves. However, gear wheels sometimes are not moved by the same synchronicity in goals, and fingerprints are not always collected in the landing areas, making arrivals in Italy and Greece a sort of lottery where, with a bit of luck, the single migrant gets the chance to seek asylum in countries with a richer and more inclusive welfare systems and a more flourishing labor market.

Sbarco, 2015 (Francesco Piobbichi)

The rise of the hotspot approach

In this context, a reorganization of practices is drawn up through the European Agenda for Migration through the development of what will later on be known as the “hotspot approach”. The Hotspot is both the name of a set of procedures to govern flows (relocation, fight against traffickers and cooperation with third countries under the phenomenon usually referred to as “outsourcing of borders”), as well as physical sites, “hotspots” where these procedures take place with the “collaboration” between national authorities and European agencies, in particular the European Asylum Support Office (EASO), Europol, and especially Frontex (the European Agency for the oversight of Continental Border Areas). The primary goal of the hotspot approach is certainly to achieve full identification of the people who have landed, i.e. fingerprint collection in 100% of cases and the distinction, well know by now between “asylum seekers” and “economic migrants”, now synonymous with “clandestine” at the margins of society and thus ugly-dirty-and-bad. The distinction would help direct the first ones towards open hubs (SPRAR [protection System for Asylum Seekers and Refugees] and CAS [Extraordinary Reception Centers]) for which a separate chapter should be opened and the others toward closed hubs ready for repatriation, whose upgrading has been one of the objectives of the EU at least since 2013 with the issuance of the “repatriation directive”.

Established in Italy and Greece since the autumn of the same year, hotspots as physical structures and approach become the object of strong criticism, very little present on mainstream media. In Italy, the old CPSAs (First Aid and Reception Centers) in Pozzallo and Lampedusa, along with former Cie of Trapani-Milo, become hotspots in no time. The fourth will be then the hotpot of Taranto, the only one in non-island territory, which, unlike the other three, is composed of non-fixed structures (tents and containers) placed in an area between the sea, the port and the industrial area of Taranto.

We will see the particular role played by the Puglian hotshot during the various episodes, but what we are interested in for the moment are the paradoxical effects that the hotspot system has created: from the very first moment it was stressed that the hotspot lacked a legal framework defining it as a structure and regulating its management issues, ranging from the question of detaining people who did not commit crimes to the ambiguous and famous “use of force”, repeatedly suggested by the European Union to Italian law enforcement agencies in order to obtain fingerprinting.

Secondly, the counterpart to the repression of the hotspot approach, defined in the form of relocation of asylum seekers (only nationals of certain countries) from Italy and Greece to other European countries, did not work according to the intended system.

Frontiera – Il muro tra noi e loro (Francesco Piobbichi)

Inclusion Lottery: Procedures and Contradictions in Access to Asylum

Finally, but maybe it is this the most relevant aspect, the distinction between “economic migrants” and “asylum seekers” on which the hotspot approach relies is not only scientifically unsustainable, as the reasons sometimes intertwine in such a weighty fashion that one cannot identify two distinct phenomenologies of migration, but also because such distinction, made at the physical site of the hotspot, actually shifts the decision on the asylum request from the legal to the police level, giving individual officials a power that seems to be in conflict with those so paraded liberal democracy schemes. In fact, especially in the early stages of this new approach, a brief interview conducted inside the hotspot was nullifying to the future of the migrant.

The main point of this interview was a question about the migrant’s working intentions: the migrant was asked if they intended to work in our country in the future. Obviously, even an asylum seeker would answer yes since a) they do not want to give the impression of a parasite and b) because they would obviously want to develop an autonomous life in the country in which they are forced to settle as a consequence of their escape. However, this procedure, later on replaced by more accurate, but equally ambiguous schemes, led to the issue of expulsion orders for many people labeled in no time by a police officer as “economic migrants”.

Many have received a deferred expulsion sheet that sets a time limit (usually 7 days) within which the migrant must appear at the border and leave voluntarily. This mechanism has led some to challenge the expulsion after being intercepted by various networks of activists in the area; on many others we have no news and we can imagine that they have ended up enlarging concealed underpaid jobs in agriculture or construction. [As it emerges from the stories collected directly which will be the subject of the next episodes]

In short, the hotspot approach as part of a larger system for migration control proved to be one of the main nerve centers of what appears to be a repressive attitude, sometimes combined with a sort of disturbing (and very often arbitrary) parallel law system for migrants in terms of detention and decision, as we will see in the next section, showing the role of the Taranto hotspot.

Per il 3 ottobre, 4 anni dopo (Francesco Piobbichi)

The “European Migration Government” column is organized by OSVALDO COSTANTINI, an associate researcher at the Center for Religious Sciences of the Bruno Kessler Foundation, which is involved in the lifestyle and conflicts research lines. Within this interest moves between scientific publications and public press releases, especially in relation to those aspects of the #migration more closely related to the imaginations, the desires, and the related frustrations and disillusionments that move the actions of these new “damned of the earth”.

Other ARTICLES: