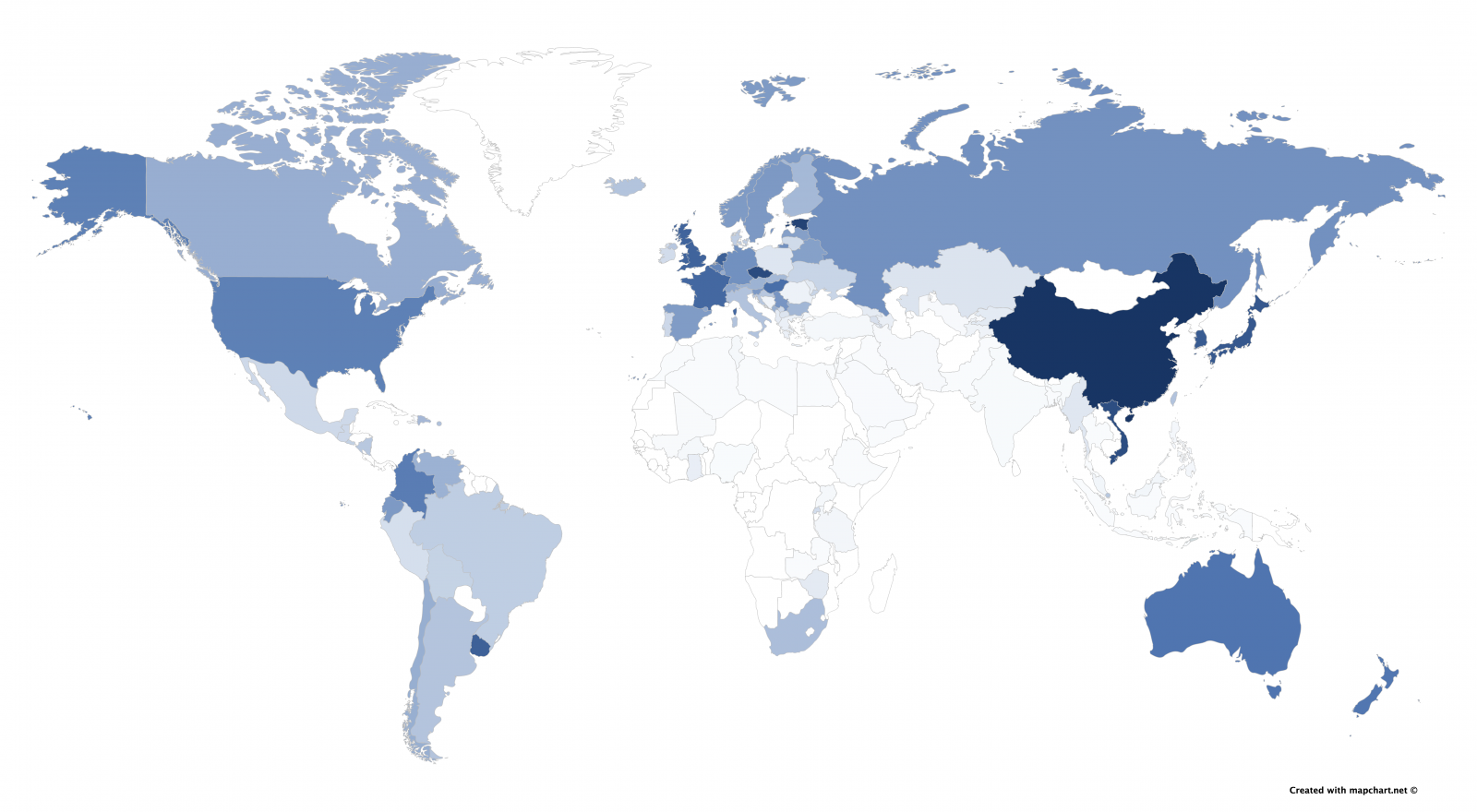

Religious nones around the world

The category of non-affiliates, the so-called religious nones, includes all those who declare that they do not belong to any religious denomination. The highest concentrations are among men, among people under the age of fifty, among highly educated individuals and among those who reside in urban areas.

The report “Mapping Religious Nones in 112 Countries: An Overview of European Values Study and World Values Survey Data (1981-2020)”, recently published on the FBK-ISR research center website, provides an updated overview of the distribution of non-religion in the world between 1981 and 2020.

The category of non-affiliates, the so-called religious nones, includes all those who declare that they are not members of any religious denomination. Non-religious affiliation therefore does not imply an absence of beliefs, be they religious or secular.

The analysis uses the recent data from the two international surveys European Values Study and World Values Survey and highlights some socio-demographic characteristics frequently associated with non-affiliation: its greater prevalence among men, among people under the age of fifty, among highly educated individuals and among those residing in urban areas. This phenomenon is particularly present in Europe, Eastern Asia, North America and Australasia; while Africa, the Middle East and some areas of Western Asia are instead characterized by a much lower percentage of nones.

Compared to the average of non-European countries, the European case is characterized by a wider spread of the phenomenon – especially since the early 1990s – and by a higher level of secularization of nones. In fact, in non-European countries, non-affiliates tend to adhere more to religious beliefs, participate more often in religious services and to attribute greater importance to God in their daily life. In 2017-20, Europe recorded a non-affiliation rate of 30.2% against an average of non-European countries of 21.7%.

The report highlights the importance of overcoming the traditional binary distinction between religion and non-religion to analyze the different forms of religiosity, non-religiosity and religious indifference that have emerged in contemporary societies. A greater understanding of this phenomenon will also improve our knowledge of other aspects of social reality frequently correlated with the religious dimension, such as trust in institutions or electoral participation. If the data of large international surveys make an in-depth analysis of these new forms of belief particularly difficult, the exponential growth of the Big Data sector constitutes a new opportunity for the development of the sociology of religion.