Education

Also Kessler went to school, but what do we know about his education? Receiving education for him was not easy for sure and perhaps this is the reason why he later on put a lot of his attention on culture and education

Also Bruno Kessler went to school. A trivial statement, especially in a region such as Trentino where access to school education was widespread as early as the nineteenth century thanks to Teresian reforms and illiteracy in the aftermath of the annexation to Italy (1918) was almost non-existent. Still, it’s not trivial to figure out what school Kessler attended. At the age of six, when his father died, he moved with his family from Vermiglio to Terzolas, his mother’s native village, where there was a Capuchin convent that could provide help to the widowed Kessler. Because of this, his elder brother was soon sent to boarding school at the friars’ in Trento. However, the same did not happen right away for Bruno, who still remained in Val di Sole, probably attending the village school, although I have not yet been able to find archival traces of this stay.

Instead, he arrived at the Seminario serafico seminary of the Capuchin Friars in Trento on September 14, 1935, at the age of 11.

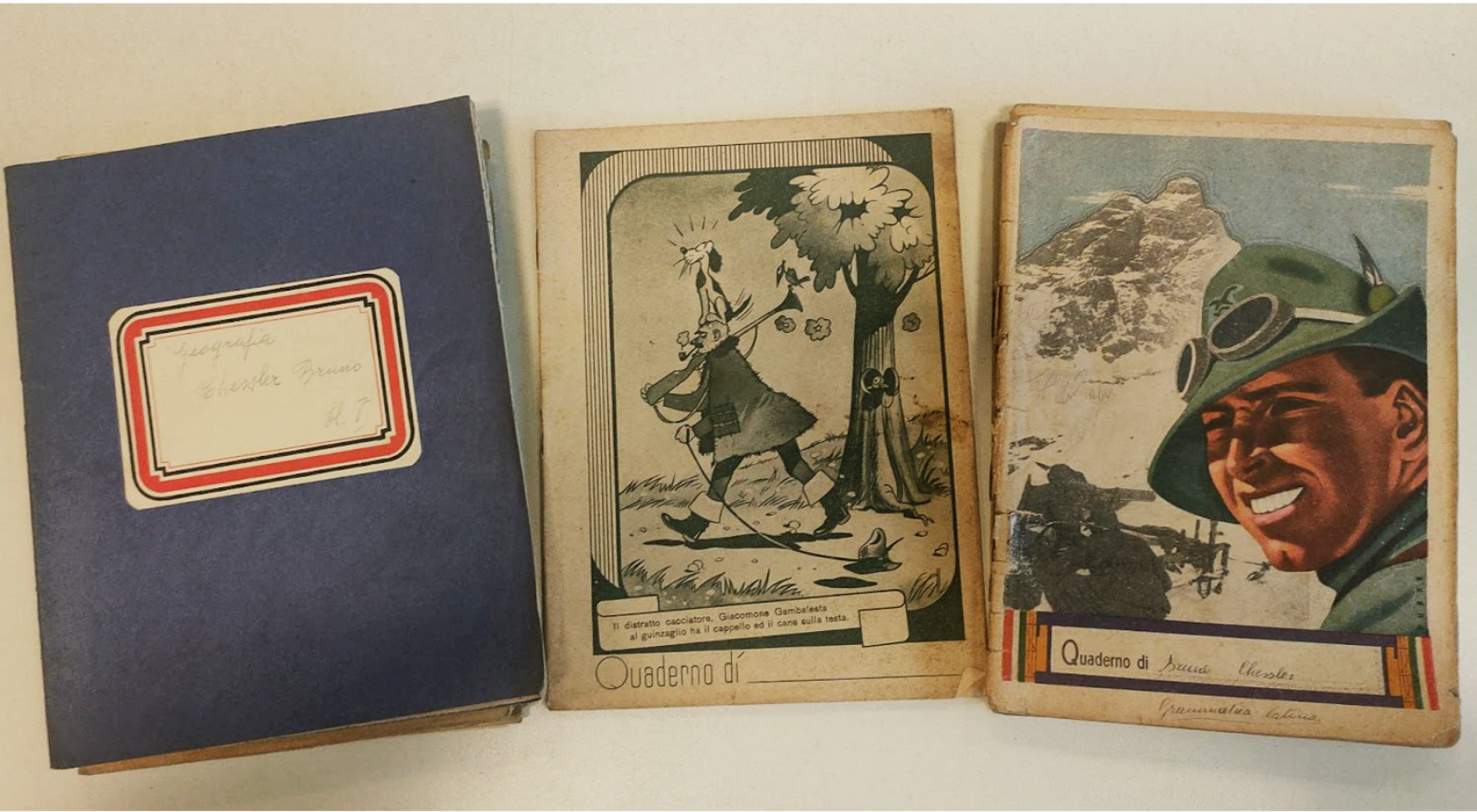

As I have already told you before, the Kessler fund actually contains few sources from the first part of his life. Among these, however, there are some school notebooks of different subjects. The name Bruno Chessler (on the variants of the surname I have already listed here) is always written in beautiful handwriting, on plain notebooks and on more particular ones, such as the one with the absent-minded hunter cartoon. More interesting are the contents of those lessons, which give us an idea of the culture in which Kessler was raised. A primarily Catholic culture given his long stay in Capuchin institutions.

Bruno had followed in the footsteps of his brother Onorato up to the novitiate, which he had completed under the name of Brother Donato; at that point, their paths had split: while Onorato had confirmed his vows and become Father Angelico, Brother Donato had become Bruno Kessler again in 1944. In fact, he remained at the Capuchin’s institute only until May 8, 1944, and then moved to the local high school for classical studies, where he obtained his diploma a few months later.

Also this research was not a trivial one. In 1944, Trentino was, like the rest of Europe and the world, struggling with World War II and also education suffered from that state of war agitation. High schools operated thanks to branches spread throughout the valleys. Thus, I found proof of passing the high school final exam, with a grade of “nine” in Italian and philosophy, only in Kessler’s university records.

Leaving the convent in those years, however, meant a call to arms. Kessler was then enlisted by Todt, a German construction company that employed forced labor, recruiting in the valleys of Trentino at the time of Alpenvorland (Nazi Germany’s direct administration of the region) draft classes not otherwise employed. Even on those railroad yards, particularly the one at Pont dei Vodi (which I have already mentioned), it is said that his hunger for knowledge had not stopped: “Between bombings he always had a book in his hands,” Giampaolo Andreatta wrote (Bruno Kessler. No al Trentino piccolo e solo, page 13).

When the war was – almost – over, Kessler enrolled in the University of Padua: law course. In law school he met some of his most important later collaborators such as Enrico Bolognani, but especially Beniamino (Nino) Andreatta Jr. It was precisely the friendship with the latter that was key to Bruno’s future, both because Nino introduced him to his father, and from there to his first job at the Banca di Trento e Bolzano bank, and because he provided support with his skills and ideas throughout his entire political career.

Kessler didn’t attend classes for long, though. His economic situation did not allow it. He had to work, for himself and to provide for his family, which he slowly managed to bring to Trento from Val di Sole. First he worked as a laborer, then he found employment at the Trento courthouse. At one point, given the difficulties of attending classes in Padua, he asked for a transfer to Ferrara for both university and work. That possibility did not realize; in the early 1950s Bruno resumed giving exams with great energy. He succeeded in graduating with a thesis on “The Putative Circumstances of Exclusion of Unlawfulness with Special Regard to the Exercise of a Right, Legitimate Defense and Reaction against the Arbitrary Act of a Public Official” on February 25, 1953. Noteworthy, given the issues he faced in his political career, is the fact that he attended the first edition of the summer school of the Paduan law school in Brixen in 1952. It was an initiative created to promote relations, including academic relations, with the South Tyrolean German minority; that first inauguration was attended by hancellor Guido Ferro and the then Minister of Education, future president of the Republic, Antonio Segni.

A worthy education background, then, especially for an orphan who grew up in an outlying valley, although he had never considered himself a man of culture. His school experience also helped shape his political vision and strong conviction about the importance of culture for communities; in 1961 Kessler, already president of the province, said in fact:

“Perhaps precisely because of this, perhaps above all because of my own particular experience of life as each of us has, I feel the value of this culture, more than being able to say exactly or well, I feel the profound value of this culture and I feel above all that our people, the men of our valleys need to be further helped in this area because any elevation in them can only come from the attention we pay to these areas.”