Fifty years ago

In the 1973 provincial budget, we find the first small steps of the Italian-German Historical Institute, the oldest research institute in what is now Fondazione Bruno Kessler

After a brief pause here we are again recounting the progress of my research into Bruno Kessler’s life. The research has never stopped. It has just reached a… slower phase.

Going over Kessler’s biography, I now found myself dealing with his entry into politics in 1956. Actually, his experience in the ranks of the Christian Democrats had begun much earlier. In 1945, at only 21 years of age, he was already the president of the Terzolas section. Terzolas was his mother’s village, where he had grown up and where the by then older Giovanni Ciccolini, one of the most important representatives of the previous season of the Popular Party, lived. It was probably through his intercession that the young Kessler approached the DC, but as he was busy working first in the courts and then at the Bank of Trento and Bolzano, he did not actively participate in politics until 1956. At that point, he was encouraged to run for election as a representative of the young Christian Democrats, and he was elected with an impressive 5,784 votes (coming in as the twelfth most voted). Thus began what would turn out to be a brilliant (and rapid) political career: already in the first legislature, in fact, Kessler was councillor for finance in the Province of Trento and DC group leader in the regional council.

The sources from this period are quite boring: they are mainly minutes of party meetings, in which the young Kessler still played a marginal role. Still, they are important pages because they allow us to see the behind-the-scenes workings of our democracy, also at the local level. Important pages, especially because they deal with a very delicate period of the history of our region (the South Tyrolean crisis and the process that led to the Second Statute of Autonomy).

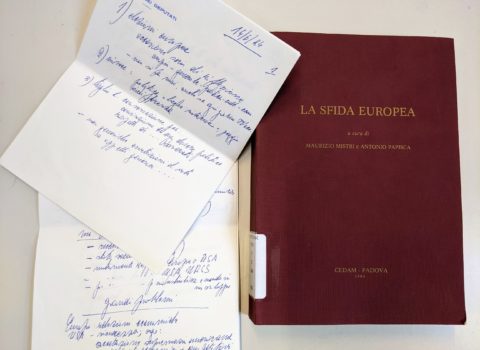

Since this is a time of financial statements, at least for the public administration, I thought I could offer you a reflection on one of these sources that, even if somewhat less exciting, talks about the end of Kessler’s political experience in the Province of Trento: it is late May fifty years ago, in the provincial council the budget is being discussed. It is not just any budget, however: it is the last of the legislature, but more importantly, 1973 is the first year after the approval of the autonomy statute: the first, in short, in which the province has the powers that previously belonged to the region. The exact figures have not yet been finalized, the implementing rules neither, but the change is impressive and the provincial council is preparing to act on its new powers. In a very long speech, Kessler lays out his plan for the province: he talks about the work done in that third term as president, but also about what he would like for the future. “The Bible according to Kessler,” as the Alto Adige headlines. In that plan there is also a part of our history: the last of the proposals presented is in fact the creation of an Italian-German Historical Institute. A research institute that, created within the Trentino Institute of Culture, would work alongside the university and exploit a fundamental characteristic of Trentino: being a meeting point between the Italian culture and the German culture. Enhancing a typical local feature meant, for Kessler, removing the university from the periphery and giving Trentino a new centrality. Attention to history was actually essential to understanding the present.

With the budget approved, the first steps were taken to create the structure that we know today. As library colleagues told us, the first book was purchased on June 4, 1973. In September, the then Trentino Institute of Culture approves the establishment of the Italian-German Historical Institute. On Nov. 3, Kessler and Paolo Prodi, rector of the university, who is co-deviser and secretary of that institute, inaugurate its activities at Villa Tambosi.

On that occasion, Kessler summarized the reasons behind that decision as follows: “In this general framework we believe that scientific research, and in particular research in the field of history, is one of the most valuable cultural goods, or rather the main cultural good without which even other goods risk remaining lifeless museums”.