From the hotspot to the street. The story of two women from Comoros

Last episode of the column by Osvaldo Costantini on the European migration government

This last stage of the path undertaken so far opens a more general reflection on the phenomena described so far that will explored further in the next article dedicated to the conclusions, articulated through references and different disciplinary looks.

The story told here is not based on a direct testimony collected among the migrants of Ventimiglia, but deals with an episode that activists of the S.T.A.M.P. (Support for People in Transit Migrants and Refugees) project shared with us.

In April 2017, STAMP is in Taranto conducting a monitoring of hotspot practices, in collaboration with the “Campagna Welcome Taranto” local collective. One of the practices on which the project has focused is that of “not entering”: it is a small pen-written annotation made by the local police on the notice sheet produced by the Immigration Office upon arrival at the hotspot. This small mark indicates that the subject in question is not being granted access to the hotspot. It is applied to some categories: people who should leave the territory within 7 days because they are subject to deferred rejection order, or those who are waiting to be transferred to a “CPR” (Permanent Repatriation Centers) or, those who have lost the right to reception following the abandonment of the center in which they were waiting for their asylum request to be processed or those who are not willing to apply.

One of the cases collected by activists during their stay at the Taranto station is paradigmatic of the dynamics that are activated in non-entry cases. Two women from the Comoros Islands – a small archipelago of the Madagascar complex, populated in the 6th century by Bantu people, colonized by the French in the 19th century and became independent in the 1970s – had turned to the activists of the STAMP information stand to present their personal problem. The two women had been captured in Ventimiglia, from where they intended to reach a relative of one of the two in France. It is not clear, however, due to the lack of a common language between them and the activists, whether the capture had taken place in an attempt to cross the border or in a police raid in the town. In any case, the two women had been transferred to the Taranto hotspot for identification. In Taranto, the immigration office had produced the notice sheet with the pen written the note “not entering” to which a second sheet had been added with the following text, in Italian only:

“The person in question is invited to appear at the police station in Bologna – Immigration Office, on xx/04/2017, to regularize their position in the national territory in relation to the request for international protection formalized in the aforementioned police headquarters”.

The sum of the two sheets and Ventimiglia’s raid, with subsequent deportation to Taranto, sheds light precisely on the mechanism of production of vulnerability we described several times: on the one hand, a sheet prevents entry to the hotspot and suggests the need to go to Bologna to complete the asylum application; on the other hand, the free circulation on Italian and European territory is effectively forbidden through the application of police operations that go beyond the regular legal system. Let us recall that it is not questioned for asylum seekers, regardless of whether the country of competence of their asylum application remains the first port of call.

In other words: the asylum seeker must remain confined where the European migration government has told him to stay: every attempt at self-determination is blocked.

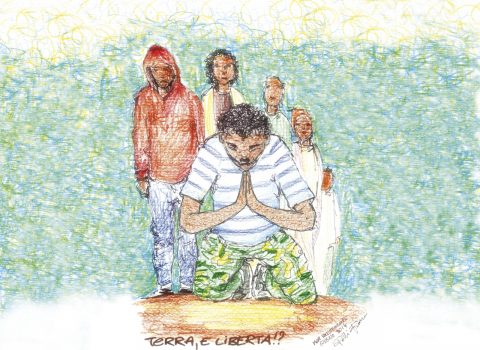

The two women were led by the police to Taranto where they cannot enter the hotspot and do not have a place to sleep, thus being forced to go to Bologna where the document invites them to go. Bologna would offer a reception centre, perhaps a CAS in the backcountry, but they have to get there and the two women do not have the money to pay for the train ticket. It is Friday when they get to Taranto, the appointment at the police headquarters in Bologna is for the following Monday. Where they will sleep and how they will go to Bologna becomes the main concern of the two women and of the activists. Various phone calls make us aware of the difficulty of finding them a place for the night until a local association offers the opportunity to keep them indoors at night, although without bed or blankets. The moment of enthusiasm faded a few hours later when the activists lose sight of the two Comorian women and later find them in the company of a group of black men at the entrance of an abandoned church… More than a suspicion, a certainty that freezes enthusiasm and reveals a complex of factors that ends up producing exploitability.

The story shows another aspect of the mechanisms that we have observed during these episodes: the parallel law system used for migrants, made of deportations and production of vulnerability, is deployed, in this case, in the application of other forms of exploitation, through blackmail-induced work by local and migrant criminality. Once again, it is necessary to observe these mechanisms, only apparently marginal, as apparatuses of those practices that are central to our social and economic life. Just as the low-cost labor of foreign farmhands in Southern Italy countryside is what allows the production of low-cost food items sold in our supermarkets, female prostitution also becomes a profitable economic tool that invests many significant spheres, e.g. the production of economic support to families in the countries of origin through remittances sent to Africa, which in some countries correspond to an economic value higher than the national product and international aid.

Once again Ventimiglia has proven to be a privileged vantage point to sort out the constitutive mechanisms of material Europe, with its relations of economic and humanitarian interdependence. Space where the relations of force, based on class or biological differences, are exposed in all their contradictions. It is precisely in those areas with exception status, where the forms of life are extreme, that the production of blackmail target figures feeds the well-being of the advantaged sections of the population.

The reported case was published in the dossier produced by the STAMP project in collaboration with “Un ponte per …“.

The “European Migration Government” COLUMN is edited by OSVALDO COSTANTINI, an associate researcher with the Center for Religious Studies of Fondazione Bruno Kessler, involved in the lifestyle and conflict research lines. As part of his interests, he writes scientific papers and participates in public press events, especially in relation to those aspects of migration more closely related to the imagination, the desires, and the related frustrations and disillusionments that move the actions of these new “damned of the earth”.

PREVIOUS ARTICLES:

Stories of (induced) marginality

Ventimiglia between official reception and informal paths

Earthly frontiers, unearthly worlds

The Maritime Alps

Hotspot hemisphere

The European government of migration