When the media make history

The ISIG 2019 summer school has involved modern and contemporary history scholars in an intense debate on ongoing research projects and scientific investigation methods

My definition of media is very extensive;

it includes every technology that creates extensions of the body and human senses, from clothes to computers.

Television brings the brutality of war into the comfort of the living room.

Vietnam has been lost in America’s living rooms, not on Vietnam’s battlefields.

The new electronic interdependence recreates the world in the image of a global village.

Marshall McLuhan

The participants (ISIG researchers, other invited speakers and selected scholarship recipients) had the chance to illustrate the historiographical sources object of their studies and to attend the presentation of ongoing historiographical research by exchanging opinions and gathering useful advice especially in terms of methodologies to borrow or to adapt.

The subject of the school was the link between the media and history. It was therefore an important opportunity for training and discussion that was scheduled within the three-year period 2017-2019, during which ISIG’s research focused on the concepts of “media coverage” and “mediatization of history”, with a particular focus on the transnational and interdisciplinary dimension.

The term “media coverage” refers to a series of long-term historical processes, marked by a growing permeability of society to the influence of mass media and the self-perception that society develops through the media. Basically, the change in the media – in the context of the socio-political and cultural transformations that characterized the modern and contemporary era – was analyzed with a multidimensional approach. Addressing the issue of media coverage from a historical point of view allows us to reconstruct the development of the media in all its dimensions (economic, technical, cultural, political) by analyzing the contents, the strategies of use and the effects that the media have produced in different historical contexts.

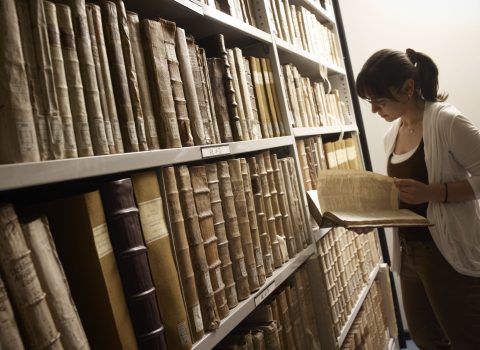

Thus, as a journey through time and space, the school allowed us to pay attention to different kinds of sources, including songs, television, radio, newspapers, and in different historical periods, from the revolution of the press in the modern age to the most recent representations of Gaddafi’s state visits to Italy.

In examining and commenting on each of these fragments, it emerged how the media are at the same time capable of perceiving (and giving back) reality and to some extent they also contribute to creating it as they tell it, becoming themselves agents of change. The history of communication can be described as a great intertwining of contents, people, means and places of information dissemination.

Moreover, as far as the richness of the sources is concerned, it has been emphasized how the intermediality can help historians in their investigative work, by mending facts and descriptions of historical contexts that are sometimes incomplete. In fact, we talk about intermediality when each medium appropriates other media, their techniques and their social meanings, and competes with their precursors and competitors. The world is increasingly becoming a mediasphere, a media system full of tensions, conflicts and contaminations. As the cinema has re-mediated photography in its time, today it is in turn re-mediated by video art, videogames and video clips, and by the many devices on which it can be seen and used. In our digital age this mechanism of remediation, which has always existed, has taken enormous and ever increasing proportions: if in the past a film could only be seen in the dark room, in a state of hypnotic and dreamlike regression, today it can be purchased on DVD, downloaded as a file, one can see sequences on YouTube, can be seen on various devices, from cell phones to tablets, from computers to the dark room. The digital image has in itself a previously unthinkable ductility, and the very structure of PCs, based on fragmentation and heterogeneity, drastically favors the convergence of the media, thanks to the window system, which helps connect verbal and audiovisual text, music, graphic animation.

Specifically, if contemporary history offers research an eccessive amount of sources, for modern history we are faced with the opposite problem: they are scarce; well, in both cases intermediality comes to the rescue of researchers and allows them to transpose the historical events through what emerges from their sedimented story on the media available at that point in time.

In this sense we can speak of an intermedial system that sees the translocal micro-history flow together. In other words, the weaving of the fragments of history, both of the modern age and the contemporary one, is inevitably connected to the cultural and media climate in which they are embedded.

The school was a precious opportunity to discuss among peers and in a senior-junior relationship on questions concerning the research method: an exchange of views and sensitivity to face the difficulties of one’s daily work. An example? The challenge of selection: what to focus on? When do you stop searching for sources and start writing?

The exchange between different perspectives and very distant research from both a temporal and methodological point of view has been useful as a mental training ground and in the space of 48 hours has enriched the instruments available to each of the participants.

In the videos made during the conference, we have gathered some key concepts of media studies from prof. Gabriele Balbi (University of Italian Switzerland) and Mariagrazia Fanchi (Catholic University, Milan) and collected the comments of scholar Vito Saracino (Gramsci Foundation) on this experience.